One Saturday morning in October 1990, 34-year-old Yusoof Abdullah made his way to the Great Hall at Wits University to be part of an event that would make history in South Africa.

It was the South African Pride March, the first of its kind in the country and equally on the continent.

“I was nervous, we were scared, there was anxiety everywhere,” Abdullah, who is now 65, says. “Some people who were at Wits Hall chose not to walk in the parade [at the last minute], they retreated when they saw the police,” he adds.

At 10:00 am on October 13, 1990, Edwin Cameron, who would later go on to become a Supreme Court judge, kicked off the march describing the various illegal apartheid laws.

During this time, the protocol for safety and protection as well as the code of conduct was also discussed.

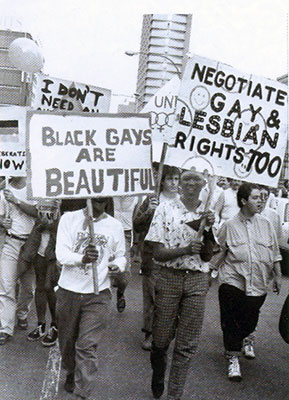

Police stood on both sides of the road where the march was taking place and although a sense of fear loomed in the atmosphere, Abdullah alongside others peacefully walked the planned route chanting slogans of “Freedom now” and “The right to choose.”

The march, which had around 200 people in attendance including activists like gay and anti-apartheid advocate Simon Nkoli and organizations such as the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW), began and ended in an estimated 90 minutes.

“Although it was a 6km walk, for me it seemed like 60km. It is the longest walk I have ever done in my life,” Abdullah says, laughing lightly.

Some marchers nonetheless could not risk exposure; they wore brown paper bags over their heads, with cutouts around the eyes, nose, and mouth.

“A number of people did not want to be identified. Some were prominent business people, others were professional men and women,” Abdullah, who was in charge of logistics, operations, and safety, explains, adding that he did not wear a paper bag over his head.

“I believed in this march. I knew I was doing the right thing spiritually, morally, and ethically,” he says.

The Immorality Act

The first Pride March was born out of defiance and a need to challenge the power structure as it existed in the days of apartheid, attendees say.

“It culminated [from] a lot of factors. It was a defiance march against segregation [and] it was a defiance march against the Immorality Act,” he explains with a hint of pain in his voice.

“[It was] inspired by the discrimination I received as a person of colour, being thrown out of my house, being unable to get on a bus, or get on and have to sit at the back; that discrimination, I can never forget.”

The Immorality Act, which prohibited extramarital sex between white people and Black people, was passed in South Africa in 1927, becoming the first major piece of apartheid legislation. It also outlawed homosexuality in public.

In 1950, the Act was amended to apply to sex between a white person and any non-white person, equally nullifying interracial marriages of South Africans that occurred outside of the country.

Two years after that, the apartheid government passed the Immorality Act amendments, which banned homosexuality. These amendments were designed to drive gay culture further into hiding.

The minority government believed that if South Africa wanted to avoid the fates of ancient Rome, and Greece, it must maintain its Christian purity and avoid ‘homosexual debauchery’.

By 1988, the apartheid government had continued to implement amendments to the Immorality Act of 1957, which further punished the LGBT community by enforcing harsher punishments to already existing sexual “crimes.”

[infogram id=”immorality-act-south-africa-1h7j4dv0ndeev4n?live”]“Pride started because of the severe statute laws that affected the community whether one was heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual,” Abdullah says. “And that’s why it was able to bring together many people from these different walks of life.”

Organisers say they realised that apartheid was akin to sexual discrimination and the march was a fight for perfect inclusion regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation.

“Pride from the onset was always a very diverse organisation,” says Kaye Ally, the Chairperson of Johannesburg Pride. “We had a collective of people; white, Indian, Colored, [and the] Black community that came together to ensure that pride started in Africa.”

Pride Today

Every year since the first event in 1990, people across South Africa – where each of the nine provinces now hosts a Pride March – and in many places on the continent come together to celebrate pride.

Today, the Johannesburg Pride is the biggest event on the continent, dubbed by many as “The Pride of Africa.”

For many, Pride is a celebration of identity, representing freedom of expression and freedom from social oppression. For Anathi Jongilanga, a queer man from South Africa, it evokes so many emotions.

“Pride has enriched my convictions and the way that I look at the world. [It] has brought comfort within myself, it brings me joy, it gives me hope that our lives will get even better in the future,” he says.

But that is not all.

“It also makes me angry that things like Pride had to happen for people to enjoy the rights they have today,” he adds.

The Johannesburg Pride as an organization has equally grown beyond the march.

Today, they curate several events like a queer fashion show, lifestyle conferences, and award ceremonies.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the organisation is also extending relief to LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees in the country from food, rent and funds for COVID testing and treatment.

“Our intention was to retain the essence of Pride, the celebration of the march, the message, and the activism while at the same time positioning ourselves beyond just that one day of the march,” Ally, who has been with the organization since 2013, explains.

On December 1, 2006, the South African government passed the Union Bill, which legalized same-sex marriage, making South Africa the first African nation to do so.

This gave homosexual couples parity with heterosexual couples for the first time. It also allowed gay spouses to make decisions on each other’s behalf, receive alimony, and adopt children

Despite securing these rights in the country’s constitution, LGBTQ+ people still face series of hate crimes, discrimination, and murders.

In April, a 22-year-old gay man on his way from his birthday party in Western Cape was raped and murdered, making him one of at least ten known gay men and Trans women who have been murdered in the last three months.

“It saddens me that given how far society has come in terms of human rights and inclusion, we still suffer hate crimes simply because we are queer,” Jongalinga says. “I hope that there will come a time when people will look at each other in their full humanness.”

Organising Pride for Kaye Ally, attending Pride for Anathi Jongilanga, and being one of the founding members of the first Pride for Yusoof Abdullah shows the evolution of this parade from a political struggle to a celebration.

“Pride is where people feel safe to be completely themselves, it has not been easy to get here, but we still have a long way to go,” Ally says.

Abdullah vividly remembers the singing and dancing at the end of the first pride. They had completed the 90-minute walk with no violence and injuries despite the police presence.

“The inclusion of the equality clause in the South African constitution in 1996 was one of the greatest outcomes of that march,” he says. “And being part of it makes me very proud.”