“Where are you really from?”: Navigating identity and belonging in the Somali diaspora

- For Somalis in the diaspora, defining identity often involves wrestling with cultural pride and the weight of outsider labels in a world that questions where they truly belong.

This photo essay was produced in collaboration with Somali Sideways. A condensed version of the series appeared on our social media pages. Read an introductory note below:

Somali Sideways is a storytelling platform founded to amplify the voices and experiences of Somalis around the world. It aims to showcase the diverse stories of the Somali diaspora, focusing on the richness of identity, culture, and personal journeys. The project encourages Somalis to share their narratives in their own words, offering a platform that breaks stereotypes and promotes authenticity.

At the heart of it is the creation of a sense of community, one that inspires future generations, and provides a space for Somalis to reflect on their challenges and triumphs. It is intended to be a cultural archive that captures the multifaceted experiences of the diaspora, whether related to migration, business, entrepreneurship, or activism. Many stories highlight the challenges of identity, integration, and overcoming adversity.

Mahamed Jama:

“It was December the 24th, the icy chill and an unforgiving cold crept through the cracks and edges of my hospital window on my 27th day of stay. Undeterred, I set out to finish my research paper before the morning nurse rounds. My eyes strayed to the blinking notification light on my phone. There were thirteen missed calls: seven from my cousins Mustaf and six from Abdalla

“It was December the 24th, the icy chill and an unforgiving cold crept through the cracks and edges of my hospital window on my 27th day of stay. Undeterred, I set out to finish my research paper before the morning nurse rounds. My eyes strayed to the blinking notification light on my phone. There were thirteen missed calls: seven from my cousins Mustaf and six from Abdalla

Despite our warm and peaceful greetings, Mustaf’s voice bore an unspoken heaviness, a deep sadness in every word.

“I just spoke with my mom and…and…um…your brother was killed last night.” Silence blanketed the room as I grappled with shock.

Without thinking, I dialed Hamza’s mobile number, hoping for some miracle, but it was my aunt who picked up, her voice merely a whisper as she confirmed the tragic news and delved into the details of his killing.

Soon after, my mother called, and I tried to comfort her, gently reminding her that death is a natural part of life we all must face. With a trembling voice, she urged me to inform my grandmother.

I faced the challenging task of calling my father to deliver the devastating news of his son’s death. Nothing could prepare me for such heart-wrenching conversations, but I mustered my courage and made the call. Our conversation was brief, the signal flickering and unstable. After our initial greetings in Somali, the exchange took a grim turn. My father met the news with an acceptance rooted in deep faith,

“We surely belong to Allah and to Him shall we return.”

The call ended abruptly before I could delve into the details. I knew the depths of pain he must have felt. He recently lost his father, a man he had dutifully cared for over a decade. His call was followed by a futile attempt to reach the rest of our family. The lines remained silent, the world outside my hospital room wrapped in the quiet serenity of Christmas Day in Sweden.

The next call was the most difficult – my grandmother. Her scream was so piercing it woke my uncle. Still healing from her son’s tragic death three years ago, she now faced the devastating loss of her grandson. I knew that this was a pain from which there would be no recovery”.

Frah Abdi:

“My parents were among the many who had to make one of the hardest decisions of their lives. To send their child away to safety and hope for a better future. I was one of many Somali children to leave in such circumstances, leaving behind your entire family with the knowledge of sacrifice, intention of betterment and the reality of life’s struggles.

“My parents were among the many who had to make one of the hardest decisions of their lives. To send their child away to safety and hope for a better future. I was one of many Somali children to leave in such circumstances, leaving behind your entire family with the knowledge of sacrifice, intention of betterment and the reality of life’s struggles.

Growing up in a foreign country without the presence and guidance of your parents comes with a lot of obstacles and challenges. At 16, I ran away from home and I remember being in the park the whole day with friends like nothing was wrong. As it got darker people started to leave until I was the only person left in the park. That’s when I realised I had no home to go to.

These challenges taught me that the only thing you can absolutely control in life is how you react to things out of your control, and there’s a lot you can’t control so the better you adapt to this reality, the more powerful your highs will be, and the more quickly you’ll be able to bounce back from the lows.

Everything that happens to you in life is either an opportunity to learn and grow or an obstacle that keeps you stuck. You get to choose. My life’s experiences whilst growing up has led me to see the value in young people and provide opportunities for them that wasn’t available to me. Alhamdulillah I work for the biggest youth organisation in the world which enables me to do the job I love and lets me travel the world.

So my brothers and sisters when life hits rock bottom, Take a deep breath; it’s going to be ok, maybe not today, but eventually. There will be times when it seems like everything that could possibly go wrong is going wrong, You might feel like you will be stuck in this rut forever, but you won’t. Sure the sun stops shining sometimes, and you may get a huge thunderstorm or two, but eventually the sun will come out to shine. Sometimes it’s just a matter of us staying as positive as possible in order to make it to see the sunshine break through the clouds again and remember Allah won’t put you through more than you can bear, he might let you bend but he won’t let you break. “

Yahya Saadiq:

“The last thing I remember before I fell asleep in the back of a Peugeot car is that my family and I were travelling from Yemen to Jeddah through the mountains of Hudaidah.

“The last thing I remember before I fell asleep in the back of a Peugeot car is that my family and I were travelling from Yemen to Jeddah through the mountains of Hudaidah.

Later, after 14 days I found myself in a room lying on a bed in a very poor condition. The only thing I was remembering at that moment was that I was with my family traveling back home. From the bed I looked through the window and I saw the mountains. My brain was telling me that there were no mountains in my neighbourhood, and started asking myself why I’m here?

Then a woman walked-in and shockingly screamed “he’s up, he’s up!”. Later on, I knew that she was my nurse and a horrible accident happened to us where our car flipped three times upside down, driver died, and my life stopped for 14 days. Doctors were telling my family that I won’t survive.

My life changed ever since I became more conscious. I got through a lot of things since the accident that made me so grateful to Allah. One of those things that I’m proud of is the Somali Community Runners, which I co-founded it with my friend Kamil. It’s basically a community of Somali Runners who gather every week to run in the streets of Cairo. Our dream is to enlarge it and have Somali Runners in every Somali community around the world. This is my way of thanking God for being here”.

Naima Farah:

I was born in Somalia and at a very young age was raised by my grandparents. My grandfather Professor Caalin was my everything. He was my hero and until today I love him more than anything. Unfortunately, he passed away few months before me and my older sister went to Finland to reunite with our mother.

I was born in Somalia and at a very young age was raised by my grandparents. My grandfather Professor Caalin was my everything. He was my hero and until today I love him more than anything. Unfortunately, he passed away few months before me and my older sister went to Finland to reunite with our mother.

My childhood in Turku, Finland was the best childhood a child could wish for. I was fluent in Finnish and had a lot of friends. Few years later, we moved to Stockholm, Sweden. To start everything all over again was pretty tough but alhamdulillah Swedish is a much easier language than Finnish.

It took me only 6 months to be fluent in Swedish. After few years in Stockholm, we moved back to Turku. I was quite happy about it because I needed to leave Stockholm behind me and start my new life in Finland.

My mom was smart to put me and my older sisters in a Swedish school in Turku but we were the only Muslims, Blacks and Somalis in the whole school. We also spoke “Rikssvenska”, the real Swedish language while in the school everyone spoke a mixture of Finnish and Swedish.

Almost every day people ask us “So where are you from?” Today I’m still trying to find a short way to explain where I’m from”.

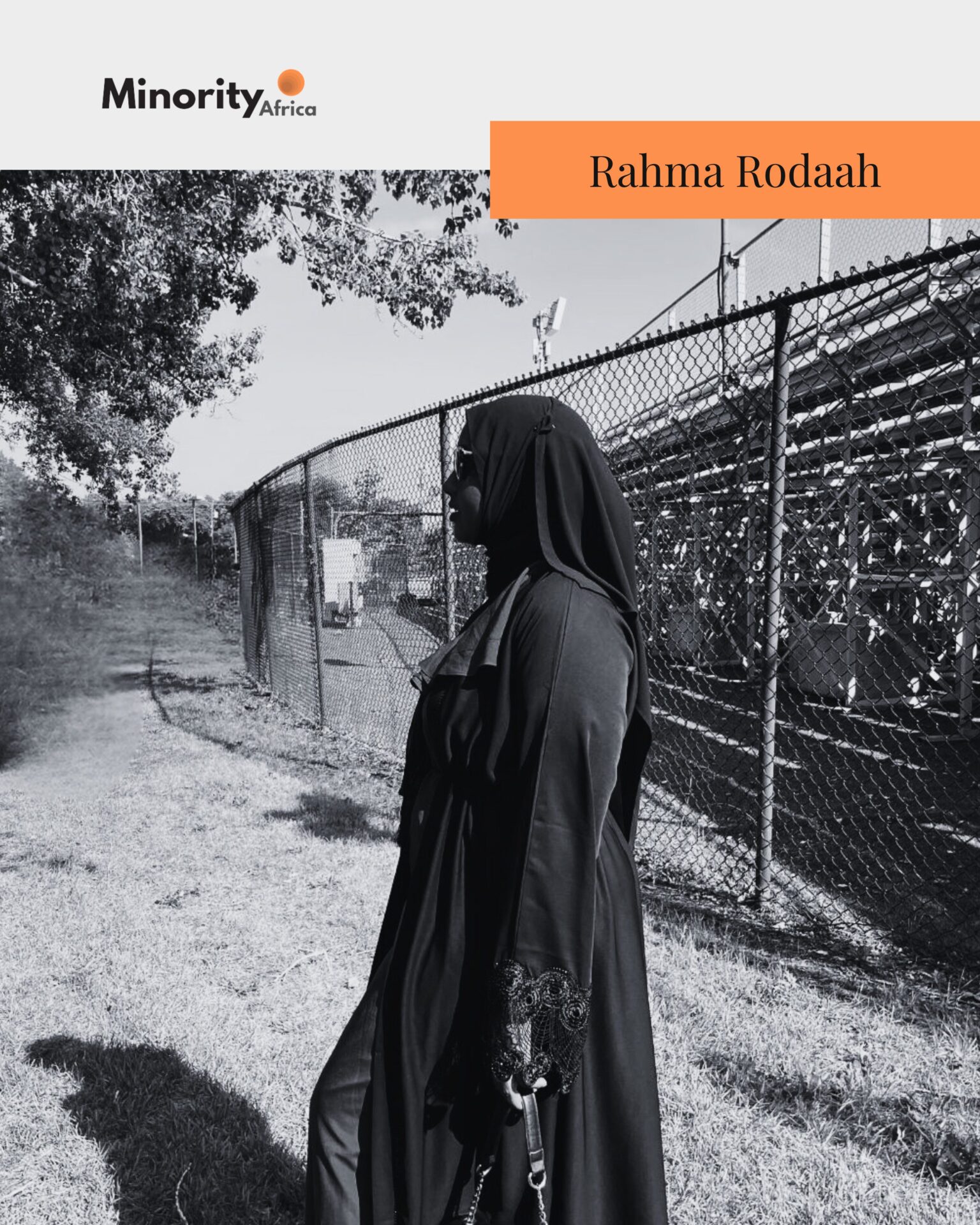

Rahma Rodaah:

“My story started when we immigrated to Canada at the cusp of the civil war in Somalia. I went from being a happy child who fit in the sea of people who looked like me and spoke my language.

“My story started when we immigrated to Canada at the cusp of the civil war in Somalia. I went from being a happy child who fit in the sea of people who looked like me and spoke my language.

My mother always recounts how early and clearly I spoke as a child. But all that changed when we immigrated, and I became the only Black Somali girl in class not talking or understanding this foreign tongue.

I got bullied a lot by teachers with their eyes and words and physically by my classmates, and I had no one to lean on. We left behind all my cousins, aunts and my beloved grandmother who raised me. My parents were drowning in their own way and fighting their own fights.

The world is made of stories. There are the stories we hear, the ones we read and tell each other. Each situation is shifted by the story that surrounds it. Each outcome is perhaps influenced by the story it began with.

Growing up, the stories I read about my identity as a Muslim were always negative. A Muslim was someone who was always radical and violent. My hijab symbolized an oppressive ideology that needed to be irradiated. As Somali, I was known to be part of a nation of perpetual conflict and rootless pirates.

Motherhood and witnessing my eldest daughter’s childhood unlocked a lot more traumatic memories I had hidden within.

My work in writing positive and affirming stories featuring Black Muslim characters is to help future generations overcome years of hurt and trauma, believing the negative stereotypes told by others.

Reclaiming the art of storytelling with a purpose to make a difference isn’t always easy, but each seed we plant in the mind of a young reader is worth the sacrifice. I write for little Rahma, who never saw herself anywhere. You made it!”

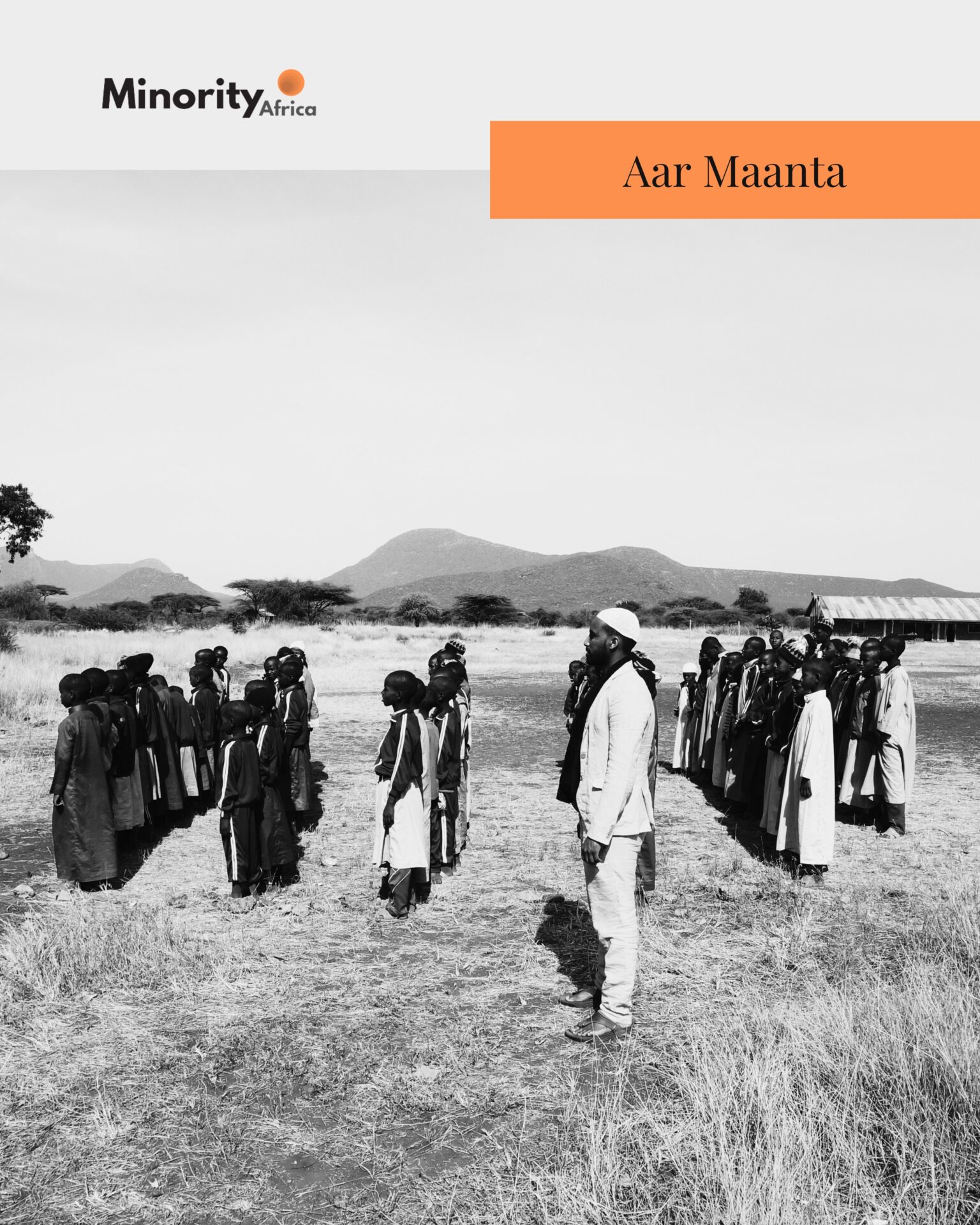

Aar Maanta:

“Be at the right place at the right time” was the quote written on the board of one of the dormitories at Wamy Orphanage where few friends and I have been doing charity work for the past few days. Many of Isiolo’s residents, a town 285km north of the Kenyan capital, are descendants of Somali soldiers who fought in World War I.

“Be at the right place at the right time” was the quote written on the board of one of the dormitories at Wamy Orphanage where few friends and I have been doing charity work for the past few days. Many of Isiolo’s residents, a town 285km north of the Kenyan capital, are descendants of Somali soldiers who fought in World War I.

I didn’t know much about this town until the morning of January 13, 2013, when I received one of the most shocking news: My best friend of nearly ten years Jamal Moghe was killed by bandits on a nearby road and was to be buried there.

Brother Jamal was a tolerant, kind and above all a forgiving individual. He was the sort of friend you could have an argument with and regardless of whose fault it was, he would always be the first to call. If you did not answer, he will call again. He never took anything to heart. It was no surprise that one of his last tweets was: “Forgive me if I have wronged you, forgive those who have wronged you, for Allah forgives the forgiving heart.”

On the night of my wedding, Jamal was my best man. Having done so much to help me prepare for my big day, I wanted him to enjoy the moment without any responsibilities. However, being the kind of friend he was, he spent the evening outside in the cold welcoming guests at the door.

Following his sudden and tragic death his widow, some friends and I have been exploring charitable options to keep his memory alive. Eventually we came across ‘Wamy School Children’s Home’ under-funded orphanage school situated under the mountains of Isiolo town – not far from Jamal’s final resting place.

One of the orphanage’s teachers remarked that they hardly had visitors so our visit alone was much appreciated. After we asked what we could do to help, they gave us a list of things. The list included fixing broken windows, buying water tank, mosquito nets, blankets, bed sheets, slippers, washing buckets etc. Thanks to money we collected from families and friends over several months we were able to provide all the items requested ourselves.

I believe all our lives are somehow connected. There was a reason why my friend’s final resting place was to be in Isiolo, there was a reason why my friends and I ended up in that orphanage. In other words we will always be at the right place at the right time for what is destined for us. However, miracles happen when we get out of our comfort zones, when we consciously and actively create chances for those who are less fortunate than us.

Let’s not rely on NGO’s or other organisations whose business it is to help others. But let’s get out there ourselves with whatever money or resources we can afford and make a difference in the lives of our brothers and sister every now and then Insha Allah.”

Edited/Reviewed by: Caleb Okereke and Sarah Nene Etim

Mohamed Mohamud is a curator, writer, and the founder of Somali Sideways, a platform for sharing authentic stories of the Somali diaspora. This initiative has brought Mohamed a global community of people celebrating the Somalian heritage while exploring themes of identity, resilience, and belonging. His work counteracts the simplistic homogeny of what it means to be Somali, thus connecting and bridging cultural gaps. Mohamed works as a freelance contributor and writer with reputable media like Africa Confidential, among others, and Geeska Platform, a platform covering in-depth analysis in the Horn of Africa. He is an African Union Media Fellow and has further magnified his commitment to storytelling by engaging African communities worldwide. Mohamed has his book housed at the libraries of Stanford University and SOAS, University of London. He holds an MSc in Politics of Conflict, Rights, and Justice from SOAS, University of London, and has traveled to over 30 countries, bringing a rich global perspective to the table.