I conducted Nigeria’s first survey on queer professionals. Here’s what we found

- A first-of-its-kind dataset from our team at EmpowerQ reveals an LGBTQ+ workforce that is young, highly educated, and systematically shut out of opportunity, despite the country’s enormous talent pool.

Illustration description: A group of colorful, stylized hands forms a circle around a golden table, each offering something to another — a laptop, handwritten notes, rolled certificates, and a small key.

Over the years, my work has centered on helping people navigate their careers and access opportunities they were previously shut out from. A lot of my compulsion to do such work comes from my own path. I was the student no one expected much from until I proved otherwise, the intern who had to create his own chances, and later, the professional who learned how often talent goes unnoticed simply because people do not fit the mould. Those experiences shaped my commitment to building pathways for people who are overlooked.

But even as I created initiatives that helped Nigerians sharpen their skills, land jobs, and position themselves globally, I knew there was a gap I wasn’t addressing. None of that work spoke to the specific realities queer professionals face in Nigeria. I had seen friends lose roles because of how they sounded or dressed. I had seen people hide entire parts of their lives just to stay employable, and I understood how exhausting it is to build a career while constantly managing risk.

I consider that to be the point at which I decided to work on a project that directly confronted the economic barriers queer Nigerians navigate daily.

In January 2025, I reached out to Adekunle Adewale Roqeeb (also known as Sasha), whose years of advocacy across Africa and Europe brought experience I knew this work needed. Together, we started EmpowerQ, an organisation focused on helping queer Nigerians access stable, dignified work through mentorship, upskilling, community support, and data-driven advocacy.

But relying on our assumptions was not enough. We needed real insight into the challenges queer professionals in Nigeria face. Very quickly, we discovered such data simply did not exist. There were no numbers on queer Nigerians in the workforce, no records on exclusion, and no visibility for gender-diverse identities. Without data, we thought, there can be no meaningful advocacy.

So we started small with a 50-person survey and used those early insights to shape our first programmes. As more people shared their stories, the scale of the gap became impossible to ignore. We expanded the survey, strengthened the methodology, and reached deeper into the community.

The result is Nigeria’s first LGBTQ+ Workforce Pulse Report, drawn from 151 queer professionals across cities, sectors, and lived realities.

Who we heard from: young, educated, and excluded

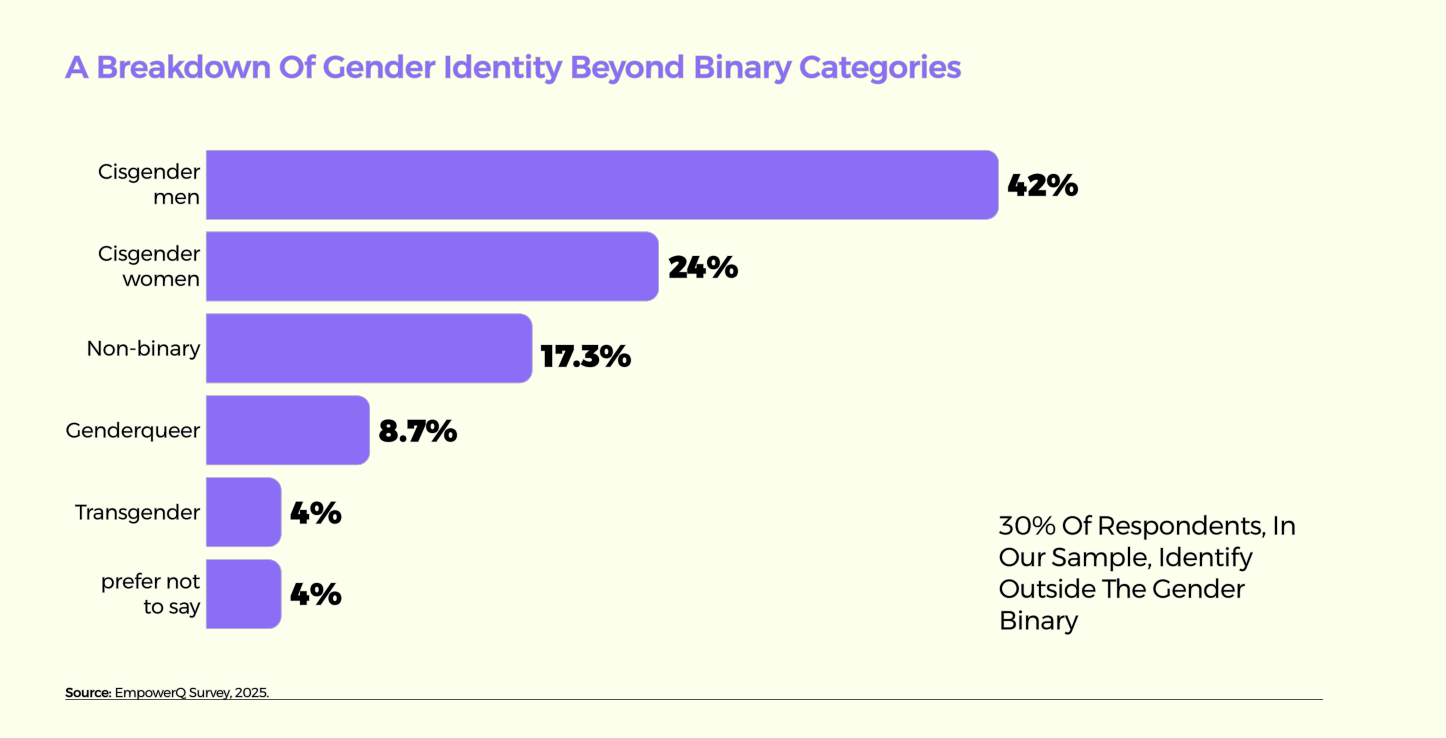

Gender

42 percent of respondents identified as cisgender men, 24 percent as cisgender women, and 30 percent outside the binary. In a country where most forms still assume two genders, this dataset offers one of the few accurate pictures of gender diversity in Nigerian workplaces. Another 4 percent declined to disclose.

42 percent of respondents identified as cisgender men, 24 percent as cisgender women, and 30 percent outside the binary. In a country where most forms still assume two genders, this dataset offers one of the few accurate pictures of gender diversity in Nigerian workplaces. Another 4 percent declined to disclose.

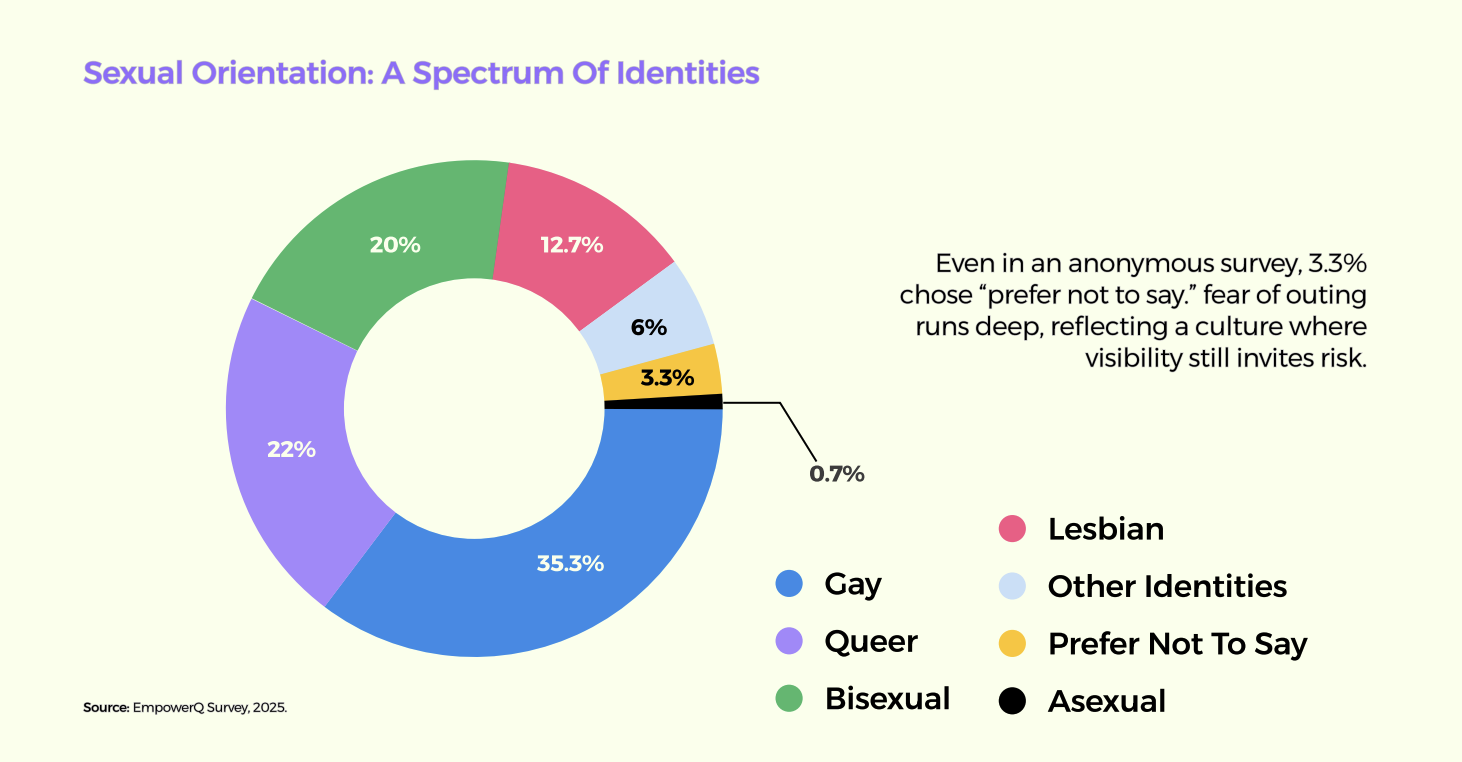

Sexual orientation

The identities shared were broad: 35 percent gay, 22 percent queer, 20 percent bisexual, 13 percent lesbian, 6 percent other identities, and 3 percent preferred not to say.

The identities shared were broad: 35 percent gay, 22 percent queer, 20 percent bisexual, 13 percent lesbian, 6 percent other identities, and 3 percent preferred not to say.

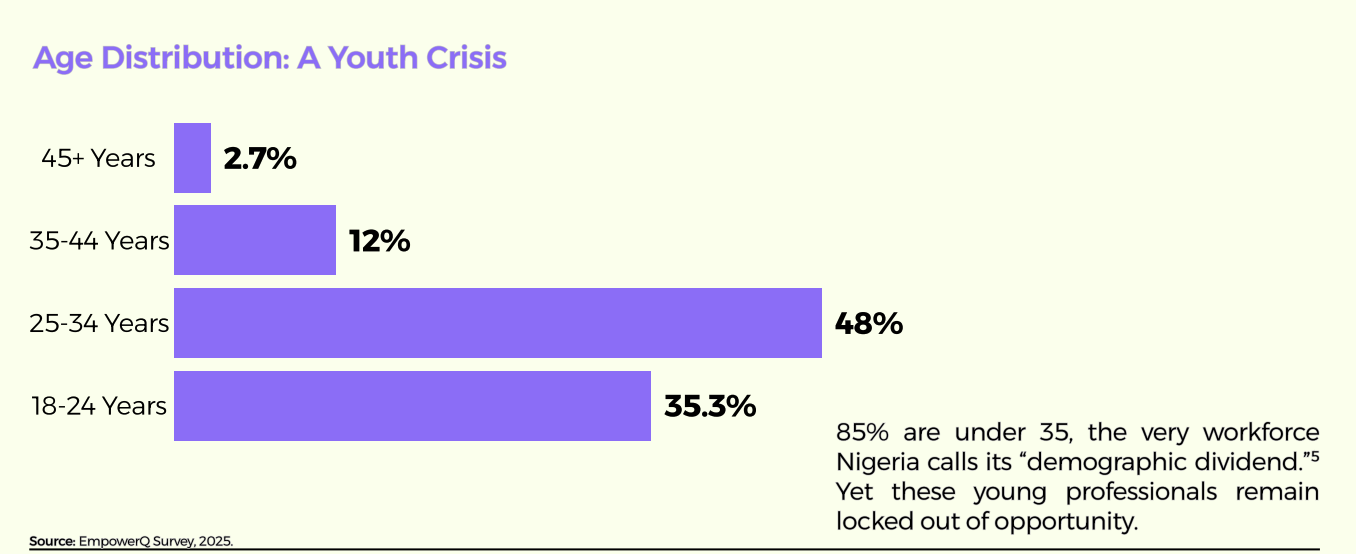

Age

Respondents were overwhelmingly young: 85 percent were under 35, 12 percent were aged 35–44, and only 2.7 percent were aged 45 or older. The steep drop after 35 hints at the pressures that may push older queer professionals into silence, informal work, or migration.

Respondents were overwhelmingly young: 85 percent were under 35, 12 percent were aged 35–44, and only 2.7 percent were aged 45 or older. The steep drop after 35 hints at the pressures that may push older queer professionals into silence, informal work, or migration.

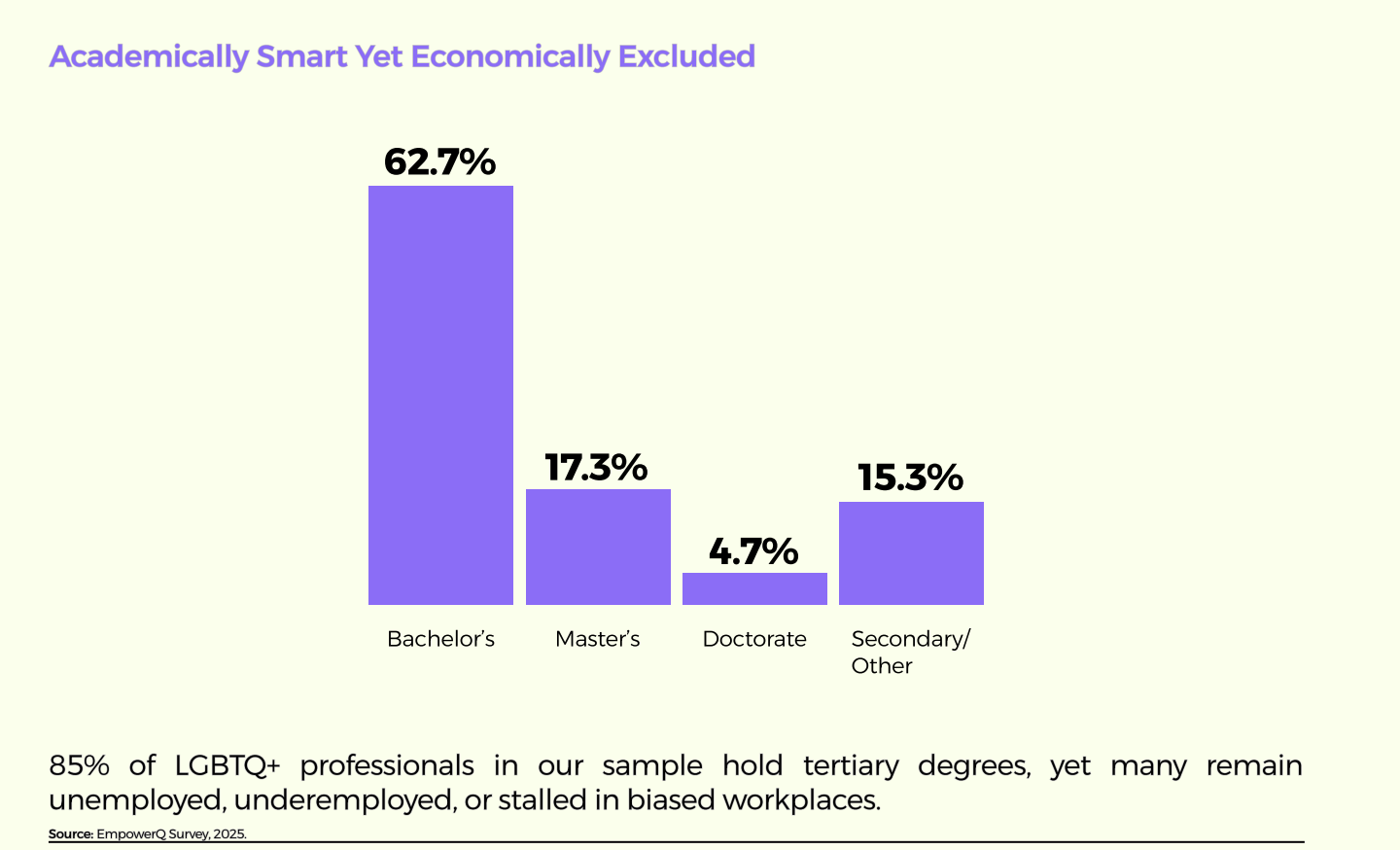

Education

Across all groups, education was the one constant. 85 percent held a Bachelor’s degree or higher, yet many remained underemployed or excluded. For many, education became a buffer against discrimination, but qualifications alone were not enough to secure opportunity.

The overqualification and employment paradox

National graduate unemployment is 22 percent. Among queer graduates in our dataset, it rises to 26 percent, despite strong academic and technical qualifications. Employers often rely on terms like “cultural fit,” “values,” or “professional appearance,” which function as coded ways to exclude queer applicants who do not conform to rigid expectations.

Respondents echoed this pattern many times. One wrote:

“I have two degrees, three certifications, and four years of rejections. My straight classmates with half my qualifications are managers now.”

Another said:

“I got tired of being better on paper but invisible in real life.”

Seeing this in the data was not surprising. Even before EmpowerQ, I had spoken with talented queer friends who could do the work but were told they were “not a fit,” even when their performance was objectively stronger.

This pattern creates double jeopardy where queer Nigerians face the same structural labour issues as everyone else, but also identity-based exclusion regardless of merit. Until employers evaluate competence rather than conformity, queer professionals will continue to be overqualified and underemployed.

Work, survival, and self-employment

The employment data shows a workforce shaped by exclusion and improvisation.

Of the 151 respondents, 39 were unemployed (26 percent), 32 had full-time jobs (21.3 percent), 21 were self-employed (14 percent), 9 worked part-time (6 percent), and 49 people (32.7 percent) had work patterns too irregular or unsafe to classify. This alone signals how unstable employment is for many queer Nigerians.

The small number of full-time workers indicates how difficult it is for queer people to enter or remain in Nigeria’s formal economy. Those who do find jobs often work in sectors where diversity is tolerated because of global influence. Tech, international NGOs, and some creative industries appear more accessible, not because they are fully inclusive, but because they offer conditions that reduce direct scrutiny.

One designer put it simply:

“Tech is the only place I could exist without rehearsing every version of myself.”

I felt this sentiment too, as one of the reasons I left the legal industry because it required a conservative version of myself, one I knew I could never sustain. In contrast, tech gave me my first taste of breathing without performing masculinity or “professionalism” in a rigid way. But even that sense of freedom is delicate, as it can disappear with a single shift in leadership or policy.

The 49 respondents with “unclear” employment status reflect the most invisible group. Many rely on gig work, informal projects, volunteer roles with stipends, or inconsistent freelance assignments. I have met several queer professionals working nonstop, yet technically “unemployed” on paper. The formal economy does not see them, which means it cannot support them.

As one web developer said:

“I earn less, but I don’t have to explain my voice, my clothes, or my life.”

Self-employment provides short-term control but comes with significant vulnerability: one discriminatory client or landlord can jeopardize income. Housing instability often compounds this risk. Minority Africa has previously documented how trans and gender-diverse Nigerians struggle to secure safe accommodation, a barrier that directly affects their ability to work and remain economically stable.

Bias, fear, and safety nets

Nearly seven in ten respondents reported experiencing workplace bias or discrimination.

Some respondents were excluded from promotions after being outed by colleagues. Others described microaggressions framed as casual remarks about clothing, tone of voice or behaviour. One person wrote:

“My manager said I act too calm for a man.”

Another highlighted how even administrative processes can erase identity:

“My NIN says one thing. My lived experience says another. Every job application becomes an exercise in erasure.”

Reading these responses was painful but familiar. Even though my own workplace experiences have been safer than most, I’ve seen firsthand how quickly policies turn into weapons when supervisors decide someone is “too much,” “too soft,” or “not a good fit.” Many queer professionals I’ve spoken to know exactly how to code-switch their way into survival because being themselves feels dangerous.

These conditions push people into self-erasure and behaviours framed as “professionalism,” but rooted in fear.

And yet, despite this pressure, queer Nigerians continue their safety nets in the form of peer circles, mentorship networks, WhatsApp job groups, and referral chains. Interestingly, information travels quickly within these networks, often faster and more accurate than anything formal institutions provide.

The solution lens

Another important thing to keep in mind from this report is that queer Nigerians are not waiting for institutions to save them, they are instead asking for the tools that make mobility possible. 87 percent want mentorship, 73 percent want stronger technical and leadership skills, and 91 percent want structured career guidance. These numbers show a community prepared to build, learn, and lead if given fair access.

For institutions, the cost of exclusion is high. Up to 94 percent of highly educated queer professionals are preparing to emigrate, representing a significant loss of skills, tax revenue and innovation capacity. Discrimination could cost Nigeria up to $31 billion in GDP over the next decade.

In contrast, inclusion produces measurable returns. Studies show that inclusive workplaces record 30 to 39 percent productivity gains, significantly lower turnover costs, and stronger innovation outputs. At the national scale, equal opportunity could unlock up to 1.7 percent additional GDP growth, alongside access to global markets worth billions, including LGBTQ+ tourism and creative industries.

EmpowerQ’s work responds directly to this opportunity. Through mentorship programs, professional upskilling, and community-led referral networks, we have begun connecting queer Nigerians to industries that are willing to hire based on competence rather than conformity. For many respondents, access to guidance is the difference between remaining trapped in unstable work and moving into safer, better-paying roles.

Alongside this, queer Nigerians continue building their own mutual-aid systems: hiring one another, sharing housing for safety, and forming savings circles to fund certifications or relocations.

The LGBTQ+ Workforce Pulse Report began with a simple question:

What would it look like if queer professionals in Nigeria had the same chance to thrive as anyone else?

We can see now that the answers arrived in different forms, yet almost every story carried a familiar undertone. Some took me back to my own journey, especially the moment I left law for tech, because it was the first environment where I could exist without constantly monitoring myself. Others reminded me of friends who had to piece their lives back together after being pushed out of jobs that refused to see them beyond their identity.

I’ll state categorically that queer Nigerians have the talent and determination needed to succeed. What holds many back are structural barriers that limit their options before they even begin. It would not be out of place to say that Nigeria now stands at a crossroads. It can continue to lose people who want to contribute, or it can build a future where talent is allowed to grow without fear.

On my own front, I know the future I want to help shape, and this report is one step toward its actualisation.

Download the 2025 LGBTQ+ Workforce Pulse Report here.

Edited/Reviewed by Caleb Okereke and Sarah Etim.

Illustrated by Rex Opara

Jeremiah Ajayi is a Co-Founder at EmpowerQ.