Niger, Nigeria (Minority Africa) — In January 2018, Malam Na’ibi, a 47-year-old Gbagyi man from Niger State in northern Nigeria, started travelling with a plan.

Malam Na’ibi, who owns an Almajiri school in Minna, the capital city of the state, decided to travel to the hometowns of each of the parents of his Almajirai to ask permission to enroll them in other schools providing Western education.

Armed with nothing but an analogy, he tried to convince the parents.

“I told them: we all have two hands. Your child is holding the knowledge of the Qur’an in his right hand. He’s meant to hold western knowledge in the left hand,” he says. “We, as Muslims, eat with only our right hand. Shall we then say because of that, we will cut off the left hand? No. Your child’s future prospects will be made bigger if both his hands are equipped.”

His tour was mildly successful, as ten out of the parents granted their permission and let him enrol the students at nursery and primary schools, even though they were all a bit overgrown for their classes. They sent him the fees periodically.

“It’s due to poverty. They did not have the means,” he tells Minority Africa. “But I knew that if somehow, they began to see it as a priority, as a necessity, they would make sacrifices in order to see them through school, that’s why I took the pains of visiting them all.”

However, Malam Na’ibi was still left with 30 students whose parents were unable to enrol them in schools. As a man of modest means himself, he could not sponsor their education. So he started to teach them himself.

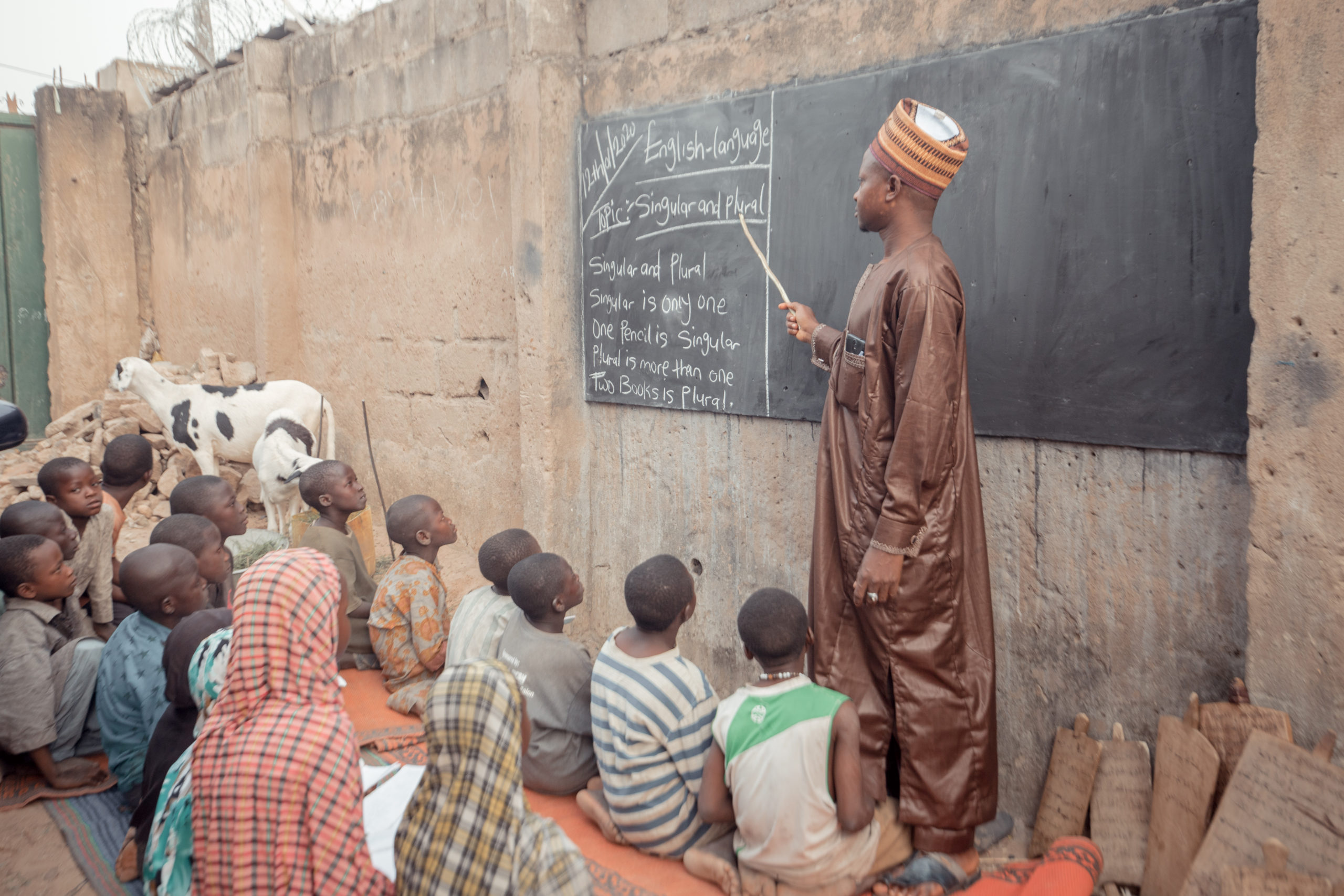

On Thursdays and Fridays, which are the weekends of their Islamic schooling calendar, he gathers them around in front of a whiteboard and teaches them basic subjects like Maths and English. When Friday lessons became too hectic because of the Jummu’at prayers, he shifted it to Saturday.

On the days he’s unable to teach them, his 16-year-old daughter, Maryam Na’ibi teaches them herself.

She is a secondary school student, and is passionate about education, just like her father. She extended the schooling sessions to Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, and twice a day: at dawn, and dusk, choosing times when they were not taking Qur’anic lessons.

“Me, I just want to be able to speak the English language. I have never missed a class since we started. I always attend. I am from Rijau, and I hardly go home. But I want to speak English whenever I go home next. So I’m really taking this thing seriously,” Ibrahim (not real name), 16, says.

He beckons to his friend who looks the same age as him. The friend approaches us.

“I attend the classes too,” the friend says. “But I am more interested in money. So I am learning embroidery and cap weaving from inside town. At the end of the day, I have little time, that’s why I am not consistent with the classes.”

When asked if he would take an opportunity to be enrolled in a school, Ibrahim’s friend nods without hesitation.

History of the Almajiranci

Before colonisation, an orderly system of education existed in northern Nigeria, where parents sent their children to teachers in faraway cities to acquire Islamic knowledge. It was known as Almajiranci, and the student, Almajiri.

The practice is done across the Muslim majority in West African communities. The state and emirs adequately funded it, alongside parents of the children, and other organised platforms, and this covered shelter, clothing, and feeding for the students. The system has since deteriorated after the British invasion and is not recognized as a regular schooling system.

In 2018, a survey jointly conducted by the Nigerian government and UNICEF uncovered daunting figures of out-of-school children. The survey says over 69% of the figure comes from northern Nigeria; this amounts to around nine million children. It also says most of the constituents of this figure are Almajirai.

A major criticism against the Almajiranci system – amongst others such as the absence of feeding, clothing, and security – is that although the students become well versed in Islamic matters, they are deprived of Western education and a grasp of basic English language.

The system and how poorly it is being run has been criticized for serious issues such as being centers where children are vulnerable and sometimes subjected to physical torture and even sexual abuse.

Malam Na’ibi’s home which houses over fifty Almajirai cyclically for 14 years is one of the many Almajiri schools struggling to find relevance in contemporary times.

For all its criticism, Dr. Hadiza Kere Abdulrahman, an expert in the field of Almajiranci, who researched the system for six years, believes that a total abolishment of the system will only escalate the problem, not solve it.

She wrote in an article for The Conversation, “Even though it is quite problematic as it stands, the Almajiranci system was once functional. It did not deteriorate to what it is in a day. A ban will not undo decades of decay, so the government needs political will and continuity. It needs to acknowledge the need for a more holistic reform across its education system, to find a way to integrate Almajiranci.”

Speaking to Minority Africa, she insists that a plural educational system like the one going on in Malam Na’ibi’s school is a better, more impactful approach.

“Almajiranci was always just traditionally, purely Qur’anic. Increasingly though, many are exposed to Boko,” she says. “What Malam Na’ibi is doing is just fascinating…this is what many of us have been advocating for; an educational plurality. Educational/epistemological plurality has to be the way forward. It just makes sense.”

“Doesn’t interfere with Qur’anic lessons”

Every day, except on weekends, Malam Na’ibi’s students assemble in clusters as early as 7 am, according to their levels of education: the beginners, which details the learning of basic things such as the Arabic alphabets and some concise Surahs/chapters.

The semi-advanced level which is usually where students, having gained an understanding of the alphabets, can recite longer chapters with ease and sometimes on their own; the advanced students are those who have completed their learning of the Qur’an and have now moved on to other books that tell them more about the religion, humanity, and science.

Some of Malam Na’ibi’s older students teach the elementary students, while he prepares the advanced students. Each of the groups arrives for classes with a high heap of scripture, awaiting their turns to be taught.

“I teach them the Qur’an, but also Seerah, Fiqh, Hadith, and Akhdari. Sometimes, I teach all grades of students, all by myself,” Malam Na’ibi says.

The lessons go on until 10 am. At night, they repeat the cycle from 8 pm to 10 pm. In a decade or more, some of these students will move away to other cities and start their own Almajiranci schools.

“I have many students that have finished from my school and gone on to other states to either start their school for other boys or learn a trade. You can’t meet them because they are no longer here. Most times, they end up doing embroidery or tailoring. Kawai, it is important for them to first acquire this knowledge before they go out into the world,” Malam Na’ibi says.

The classes are held in a space with only a cemented floor and roofing. The students unroll mats there. Then they sit in a semi-circle, leaving space for Malam Na’ibi to sit when he emerges from his room. When he comes out, they all immediately change their sitting positions to squats, eyes looking down. After he sits, they sit back.

In other settings, especially in Nupe communities, a student who runs into his Malam inside town stops wherever he is and squats, taking off his shoes and staying in that position until the Malam has passed.

Explaining the significance of this gesture as it relates to respect bordering on reverence, Isyaku Bala Ibrahim, a prominent Nupe writer and author of two books written in the language, explains:

“This has to do with the interpretation of the hadiths of the prophet on the position of a teacher or scholar to his student; a student must respect and honour a scholar or teacher. Some teachers even send their students to farm, and on other household activities like fetching water, going to the market, etc.”

Malam Na’ibi tutored under Malam Audu Nakakumi in Zaria before moving down to Minna where he, again, learned from the likes of Sheikh Nafi’u, Malam Isyaka, and Malam Garba Hakimi. After that, he started his own tutoring. He acquired Western education in Zaria, before moving on to Minna where he acquired a Diploma in Islamic studies at the Justice Fati Lami Abubakar (JFLA) college. Because he did not begin Western education until he had gone very far in Qur’anic studies, he was often the oldest in his class.

“I have plans of getting a degree from Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (IBB) University, Lapai. Or perhaps Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Or maybe Nasarawa. I am more inclined towards IBB University though because it is closer to home,” he says.

It is this experience of Western education that inspired his tour. The children also seem to be thankful to have a blend of both Islamic knowledge and Western education.

Masa’udu, 10, is from Paiko. He is one of the Almajirai whose parents can’t enrol them in school. He makes do with Malam Na’ibi and Maryam’s homeschooling. He’s been here for a year and is very enthusiastic about learning.

“Sometimes, Malam Na’ibi teaches us. Other times, she does,” he says, pointing at Maryam Na’ibi.

“It doesn’t interfere with my Qur’anic lessons. I’m even entering a new Surah in the Qur’an tomorrow.” His voice is low and shy but excited.

He has a notebook in which he takes down his notes, and revises after the class has ended. When Maryam Na’ibi reads a story out to them from a textbook, he listens with rapt attention, his eyes fixed on her, his head drawn forward in concentration. When she asks if anyone would love to come out to read from the textbook, he half raises his hand, then brings it down; willing, but unsure.

“Sometimes, other children from the neighborhood join. They are all so eager. Most of them actually just want to be able to speak the English language. Even the ones who are already enrolled in school use the opportunity to revise what they were taught,” Maryam Na’ibi says.

There are several Masa’udus scattered around Almajiri schools in Minna where the same system of homeschooling is replicated.

Dr. Abdulrahman found in her thesis that the mainstream representation of the Almajiranci system is only “one possible set of articulations and that alternative meanings exist.”

Malam Na’ibi’s practice of Almajiranci reflects this.