Cameroon’s armed conflict is asking this ethnic group to pick sides

- Caught between conflicting parties, indigenous Fulani people of Cameroon’s conflict-affected regions are forced to make the difficult choice of siding with one of the parties - and do so with devastating consequences.

Buea, Cameroon (Minority Africa) — On a chill afternoon in January 2021, a group of gun-wielding men believed to be separatist fighters besieged Orti, a village on the outskirts of Ndu, a town in the conflict-affected Northwest region of Cameroon. Aissatou, a member of the indigenous Fulani people (Mbororos), a minority and disadvantaged group in Cameroon, had prepared her husband’s favourite meal (okra and cassava paste) and was about to serve it when she heard incessant gunshots.

“We were terrified,” Aissatou, now 24, recalls. “I and my two children laid flat on the floor to escape from stray bullets. We do that whenever we hear gunshots.” Her husband had gone out to look after their cattle and had exceeded the time he would usually come home. Though worried, she was sure her husband would find his way back home amidst the gunshots as he always does.

At about 7 pm, Aissatou received the news of her husband’s whereabouts: he was drowning in his pool of blood at the village square. The separatist militia had shot him.

“I fainted immediately after I heard the news. I probably would have followed my husband if Allah had not intervened,” Aissatou says.

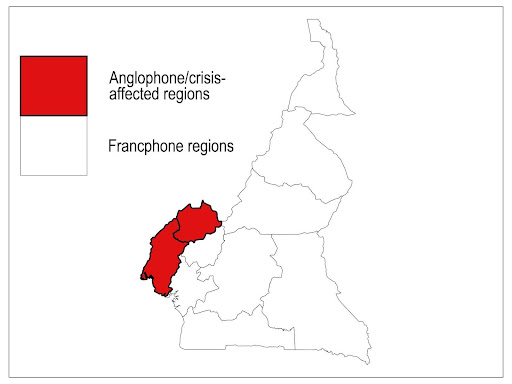

The Mbororos have been disproportionately affected by the prolonged armed conflict that has erupted in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions since 2016. A report by Amnesty International says about 162 Mbororos have been killed, 300 of their homes razed, 2500 of their cattle seized or killed, and about XAF 180 million (about $ 293,897), paid in ransom for over 102 of their kith and kin who have been kidnapped as a result of the armed conflict.

The constant violence has pushed some Mbororos to fight as militias alongside government forces against armed separatist fighters, commonly referred to as Amba Boys, who want to create a separate state for Anglophone Cameroonians.

“We don’t have a choice. We have to protect our cattle and our land from Amba Boys”, says Adamou, who fled his native, Wum, to Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest region of Cameroon, in 2020 due to constant threats and assassination attempts from separatist fighters.

Though in a new environment, Adamou is one of the main advisers and a founding member of a vigilante group in his village.

“The vigilante group is purely for self-defence. We work in collaboration with Cameroon’s military forces,” he says as he flaunts his bracelets, which he claims have magical powers and have helped him to survive numerous Amba boys’ assassination attempts. “We don’t like Amba Boys,” he says. “A top government official told us that they are out to wipe out all the Mbororos in Cameroon, and we shall not watch them do that. It would never happen,” he adds, waving his index finger in disagreement.

Historically, the Mbororos, who are primarily pastoralists, have been in perpetual conflict over land with native farmers in the northwest region of Cameroon, who make up most, if not all, the separative fighters,

Beriyuy Cajetan, a human rights activist, says Mbororos are sometimes targeted by armed separatists “just because they are Mbororos.”

“Three of my wife’s cousins, her two aunts, and 20 of my cows were killed by Amba boys before we left the village. They also threatened my life, and as a driver, it was risky for me to continue in my village,” says Aliyou Gidadoh, a taxi driver in Buea who escaped with his family from his village in Ntiswa, on the outskirts of Ndu in 2020. “Buea is comparatively safer than my village, but life here is very difficult for me and my family.”

Aliyou says he feels separated from his culture and homeland. “What makes us Mbororos is our relationship with cows. My cows, who I consider my children and also friends, have all been killed,” says Aliyou.

Still, some argue that Mbororos are a party to the armed conflict and thus deserve the constant attacks by separatists.

“Both separatist fighters and Mbororo militias have committed serious human rights violations,” says Berinyuy, who is also the head of the Department of Human Rights at the NGO Center for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA). “When separatist fighters attack Mbororo communities, Mbororo militias retaliate by attacking adjacent non-Mbororo communities.”

In February 2020, for example, state forces aided by armed Mbororo militias massacred about 21 civilians, including 13 children and one pregnant woman, in a locality known as Ngarbuh in the Northwest region of Cameroon.

“We are victims of circumstances. We have been unfairly targeted by separatist fighters”, says Musa, a part of the Mbororo community who had fled his village, Orti in 2021 but had to return after suffering from severe fire burns in Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital, early this year. “There was no way I could continue with my job. I had nobody to take care of me in Yaoundé, and I was replaced at my job site immediately when I had this accident.”

While Aliyou continues to miss his slain cows and his village as he struggles to adapt to life in his newfound home in Buea, Aissatou is battling with post-traumatic stress disorder as scenes of her husband’s unfortunate death keep flashing in her mind.

“I have a mental breakdown almost every day,” she tells Minority Africa. “This is made worse by my 5-year-old son, who keeps asking me where his father is.”

Aissatou got married at 17, is not educated and has no skills either. “I am always in tears, thinking of how I will survive with my two children. My husband’s death has left a permanent scar in my life”, she says.

Edited/Reviewed by: Samuel Banjoko, Patricia Kisesi, Uzoma Ihejirika, and Caleb Okereke.

Shuimo Trust is a Cameroon-based journalist with a BSc in Journalism and Mass Communication from the University of Buea, Cameroon. He has 5 years of progressive experience as a journalist. His interests cut across environment, politics, and entertainment. He has served as editor-in-chief of the Cameroon-based environmental newspaper, Green Vision Newspaper. He is also the Founder of a political and culture blog known as Shuimo News. Shuimo Trust has also served as a communication officer for one of the leading conservation organizations in Cameroon, the Environment and Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF). He has also written for the leading pan African Newspaper, The Continent.