A board game for refugee children in Uganda is bridging the education gap

- Uganda is one of the largest refugee hosting nations in the world, yet the quality of education in refugee settlements is still lacking. A board game is changing that.

Kyangwali, Uganda— As one approaches the classes at COBURWAS Nursery and Primary school in Uganda’s Kyangwali Refugee Settlement, the noise coming from within the rooms can be quite distracting.

Yet in this school, the noise is normal and even productive.

It is a result of a learning activity incorporated in the timetable. After every lesson, the pupils at COBURWAS engage in a game that is designed to tutor them but also allow them to have fun at the same time.

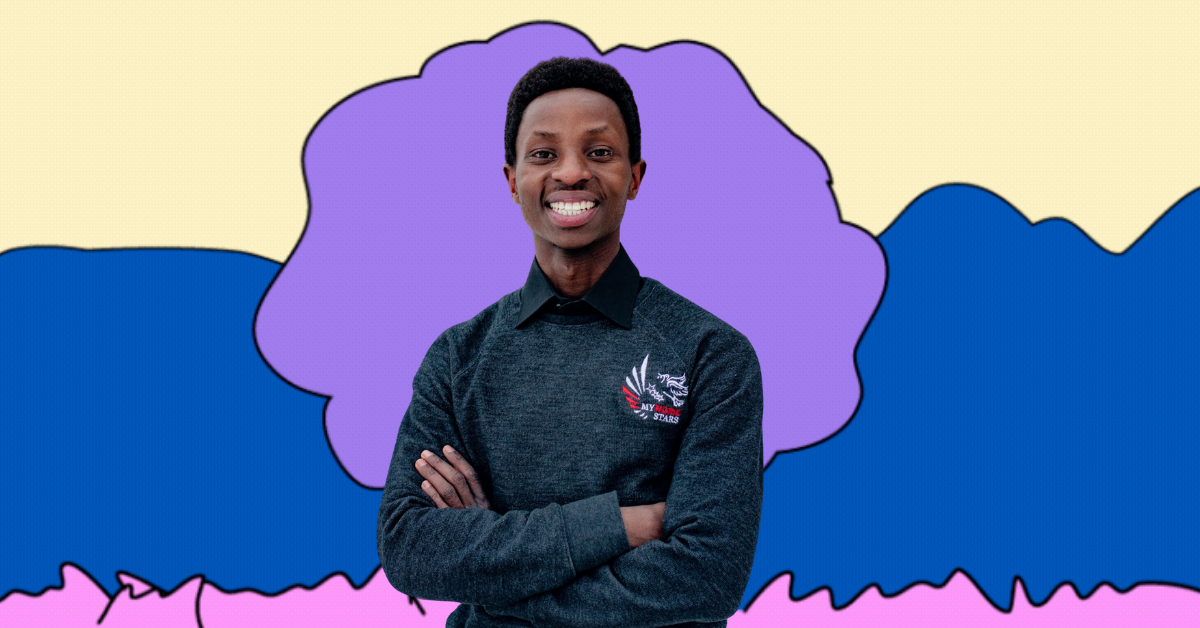

The game, known as the 5 STA-Z game, was created by Joel Baraka, a 23-year-old Congolese who was a former refugee in Uganda. It is meant to improve the quality of education offered in the refugee settlement while creating an exciting experience for the learners.

“Many in the refugee camp look forward to starting school to be able to play in a safe space,” Baraka says. “Playtime is not common in the camp because of space, so I started this game that added playtime to learning for these children.”

Schools across Uganda have been in and out of session since last year as a measure to reduce the spread of COVID- 19. The country’s Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) developed a national response plan to ensure continuity of schooling during the pandemic and learning was moved from classrooms to the television and online space.

While many learners have adopted this norm, it has further widened the education gap for refugee school-going children who have little or no access to these forms of learning.

For Baraka, the closure of schools reaffirmed the importance of the 5 STA-Z game to children’s learning and since November 2020, the settlement has received over 300 copies of the games, allowing children to remain at par with their classwork even as they stay home.

“When the pandemic hit last year, together with a colleague of mine, Anson Liow, we started a Go Fund Me campaign page where we were able to raise USD 12,000 in four weeks,” Baraka says. “Schools closing last year was an eye-opener for me; I realized that this game could help children in a big way.”

Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Joel Baraka moved to Uganda with his family in 1997, months after he was born, to live in Kyangwali.

He remembers how much he looked forward to starting school and how disappointed he was that the classroom sessions were far from the fun he had dreamt about – an experience he is aware isn’t just peculiar to him.

Over a million refugees

Uganda is one of the largest refugee-hosting nations in the world and it is home to over a million refugees. Children constitute around 60% of that number.

While refugee children in Uganda enjoy the same legal, physical, and social protection systems as the host population as well as using the same social services including universal primary and secondary education, the quality of education in the settlements is still lacking.

Characterized by congestion, many of the schools in refugee settlements lack resources including teachers, textbooks, and libraries.

“Children in the camp are always dealing with many issues like hunger because food is usually in shortage so learning can be challenging,” Baraka says with concern. “This game helps because they can still learn in a playful way and for a moment forget some of those challenges.”

This is equally the case in Kyangwali. The settlement has been in operation since the early 1960s and is home to approximately 42,262 individuals including refugees and asylum seekers.

Out of the nine public primary schools in the settlement, five of them currently use the 5 STA-Z game, which is being given out for free with the support of good-hearted donors.

Yet it is not restricted to pupils in refugee settlements.

The project, My Home Stars, is working with three other schools outside the settlement in Fort Portal and Kasese and Baraka hopes that the game will someday be available to all primary school-going children in the country.

The 5 STA-Z game comes with a die, board, and cards with questions and answers in the four core subjects of the primary school level in Uganda’s curriculum. It is played in groups of five pupils. When a player rolls a die, they have to answer the question on the card correctly or else forfeit the move.

“It summarizes the content meant to be learned for a particular year on cards,” says Ferdinant Ayikobua, who is a teacher at COBURWAS. “As the learners play, they become more familiar with what they are learning in class.”

The game board has green points and red points. The green points are known as chance points and represent opportunities. Here, when the learner answers a question correctly, they earn bonus points.

At the red points, which are referred to as the danger points, even when the learner answers the question correctly, they lose a point if the score is an odd number or divide the points if the score is an even number.

“We use the game to teach children that in life they can be presented with opportunities and one has to be prepared and focused to benefit from these opportunities,” says Eric Ogwang, the coordinator of the game in Kyangwali.

“Children also understand that sometimes you can do things correctly and not be rewarded and that’s okay too. They have to be able to move on and search for other opportunities,” he adds.

The use of games to consolidate knowledge is not new to the field of education and many experts have highlighted the importance of this.

Aarti Dadheech, an educationalist serving as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, JIET Group of Institutions in India, explains that learning is not just rote memorization.

Students won’t be able to gain any information and skills out of a dull learning process, Dadheech writes in a post on The Knowledge Review.

Expensive to produce

Growing up in a settlement might have opened Baraka’s eyes to the problem of dull learning but the idea of the 5 STA-Z game was inspired during his Advanced levels at the African Leadership Academy in South Africa – an education he is thankful to have, and a quality he wants to pass across to other children.

“I know that the opportunities I have been presented with in life have been because of education,” says Baraka, who is currently studying civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the USA.

He joined the university through the King-Morgridge Scholar program, a competitive international scholarship program that supports exceptionally driven incoming students dedicated to poverty alleviation in their home countries.

In 2017, Baraka was given a Queen’s Young Leaders Award for the practical ways he is addressing the challenges facing young refugees. He was recently among the top 10 winners of the OZY Genius Award presented to outstanding undergraduate students across the United States.

Through this recognition, Baraka and his team got funding from OZY as well as Chevrolet and the funds will be used to produce more copies of the game.

Nonetheless, with all the good it is doing, the 5 STA-Z game cannot solve all the challenges children in refugee settlements face in their pursuit of education.

Because the project depends on well-wishers, Baraka is unable to avail his game to all children who need it, at least not at this point.

There is also the cost of producing the game as well. Using manufacturers in Uganda, he reveals, has been expensive.

“We have been paying $25 to produce one game with local producers for a job we would pay $9 in China,” he says.

He hopes to continue producing locally in Uganda as a way to support the economy as he continues to find ways to decrease production costs.

The game is content-intensive, a factor that perhaps accounts for the high costs of production, but fund shortages have nonetheless caused delays in availing the game to learners.

Baraka says he and his team plan on purchasing two machines by the end of this year to lower those costs, adding that, “One machine will produce the content while the other produces the packaging for the game.”

Despite the hurdles from creation to production costs, Baraka feels the process has been valuable.

“It is so amazing watching the children playing the game. It makes the journey worthwhile,” he says, laughing heartily.

Arop Avambo contributed to this report.

Journalist at large.