When faith is expected, “it is best to keep [unbelief] a secret”

- From secret Discord Bible studies to podcast communities, Nigerian atheists find ways to connect and support each other while maintaining careful public personas in a deeply religious environment.

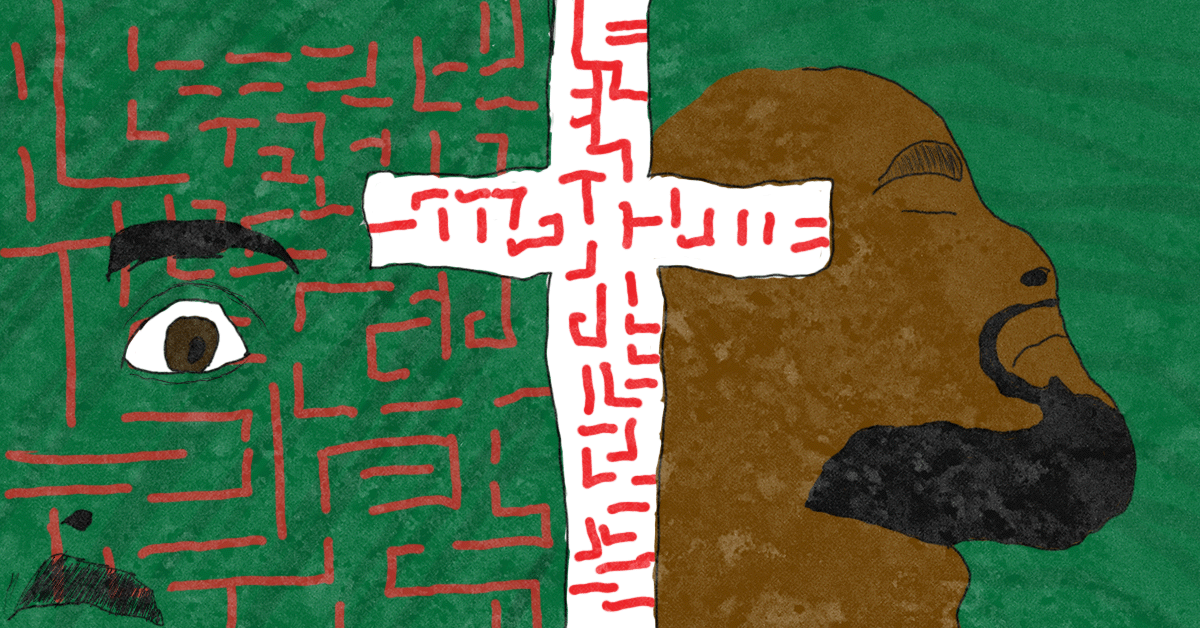

Image Description: The image features a green background – green being Nigeria’s national color – divided by a white cross with red maze-like patterns running through it. On the left side, there is a frightened face with one open eye, surrounded by a red maze, symbolizing entrapment. On the right side, a brown-toned figure with a beard and closed eyes appears to be peaceful, contrasting the chaotic elements on the left.

Ibadan, Nigeria (Minority Africa) — For most of his life, Tolu, a hospital lab technician in his 20s, was a devout Christian. In 2019, he joined a campus fellowship at the University of Lagos, hoping to deepen his faith and live a more meaningful Christian life. By 2020, however, his commitment took an unexpected turn—he began scrutinising his beliefs more rigorously, wanting to understand the core truth among the many doctrines and denominations.

“[I started asking], how can I get to the bottom of what Christianity is or what the true doctrine is? How could I further my relationship with the Holy Spirit?” he told Minority Africa. “So I kept asking myself all these questions and reading the Bible more, [but] I was seeing contradictions. I was delving into apologetics. I was doing several things to strengthen my faith, and the more I strengthened my faith the more I opened up another set of questions.”

Questioning things made it difficult for Tolu to reconcile Christianity with reality, as the things he knew were clashing. So he stopped.

“I sort of chickened out,” he said. “I stopped trying to understand. I stopped trying to read the Bible. I stopped trying to deconstruct. I stopped trying to ask questions.”

For years, he identified as a Christian—until 2023. Two years into a relationship with a conservative Christian woman who wanted a God-fearing partner, he found himself confronting his crisis of faith once more. Trying to be the good Christian partner his girlfriend wanted—and that he once aspired to be—only made it clear he no longer believed.

“It was just an issue of, you know, removing the denial. Once I got that denial out of the way, it was obvious to me that I couldn’t continue anymore.”

His transition to identifying as an atheist came after discovering Charles*, the creator of The Ranting Atheist podcast and the Discord community Nigerian Atheists, on Twitter (now X).

“He [Charles] was always tackling Christians on my timeline, so it was very intuitive why his content kept coming back to my field on Twitter. It was through his Twitter that I got to find out about his Discord community and I started attending the Wednesday Bible Study,” Tolu said.

Finding Community in Atheism

Charles founded Nigerian Atheists to create a safe, inclusive space for nonbelievers. Members share books, news, and discussions while enforcing strict rules against queerphobic and misogynistic comments. The community also hosts weekly Atheist Bible Study sessions, where mostly Nigerian and African atheists critically analyse scripture.

The study, lasting two to three hours, involves reading Bible passages and dissecting them for contradictions and absurdities—often with humour. The sessions are recorded and some are uploaded as episodes of The Ranting Atheist podcast. A recent upload starts with mock-worship songs and a brief discussion on “flat earth theory” before selected members read Genesis 35-37 from the New Living Translation (NLT) Bible.

“I got [the idea] from a podcast I listened to called Drunk Bible Study,” Charles said. “They’re two former Christians teaching their friend who is a lifelong atheist about the Bible while drinking alcohol, as having an equivalent of the Drunk Bible Study would be a great way to diversify my content.”

Charles and about eight early members of the community started the study group on Clubhouse in 2022. When the audio-only social media platform changed its interface, they lost contact with some regular attendees. So they moved to Discord in August 2023. “Now, Discord is an app many Nigerians aren’t familiar with except they’re gamers or into crypto at one point,” Charles explained. “So we needed to create a reason for the few people present to keep coming back, and Atheist Bible Study was now strictly held on Discord as a way to keep the server alive and plug guests into the community.”

The Discord server also hosts Story Of An Atheist, a long-running podcast series, where atheists share their deconversion journeys. The effort is paying off.

“The Atheist Bible Study has given me community,” Tolu said. “Living among religious people is tiring, especially considering that I haven’t come out to my family yet and have to put on a pretence. [So] having a space where a couple of heretics cannot only talk about the Bible, but a bunch of other topics as well immediately after Bible study has been refreshing.”

A Matter of Safety

According to a 2022 BBC report, 97% of the Nigerian population are religious. Leo Igwe, a prominent atheist and founder of the Humanist Association of Nigeria (HAN), the country’s first and most definitive organisation for nonreligious people, disputes this statistic and challenges its accuracy in light of the present reality.

“They [stats like that] play in line with the idea that Nigerians are deeply religious,” he said. “As a Nigerian, I don’t think we’re deeply religious. Religion goes with a lot of oppression, a lot of coercion, a lot of violence, [so] that people are compelled to identify as religious.”

For him, these people are only nominally Christians and Muslims “mistakenly” classified as religious.

“People are just going for what will get them what they want,” Igwe said. “A lot of them are religious because they want to win votes, a lot because they don’t want to be killed. Not because they are really believing people.”

Augustine Okwa, president of The Secular Community’s Nigerian chapter, agrees, saying, “People in the upper echelon of the society identify as religious to get along.” Igwe calls this “religious politics,” an indication of how atheists live in the country: mostly closeted, barely public, and only “getting along.”

Religion in Nigeria is said to be diverse. But the country has one of the biggest Christian and Muslim populations in the world, with a dominantly Muslim North and a dominantly Christian South. Besides Islam, Christianity and African traditional spiritualties, other religions include Baháʼí Faith, Hinduism, Chrislam, The Grail Movement, Reformed Ogboni Fraternity and Judaism. The less than 1% of the population who are nonreligious must therefore live in a country where religion, forceful or voluntary, is ubiquitous.

But being an atheist in the Muslim-majority North, where Sharia law exists alongside civil law, is particularly dangerous. Mubarak Bala, an outspoken atheist and HAN president, was sentenced to 24 years in prison for “blasphemy and public incitement,” later reduced to five years and was eventually released in January 2025, after four and a half years in jail. Another HAN member was recently jailed after being exposed as an atheist in a virtual meeting.

“They tried him under the state law,” Igwe said, cautious about revealing details. The HAN member was identified as a non-Muslim and was tried in a civil court. “But of course, the whole spirit of the trial was Sharia.”

In the Christian-majority South, being an atheist is only relatively safe. Charles asserts that “besides physical harm, the actual harm is financial.”

“If you’re in a place like the North where physical harm is assured, you’re highly advised to shut up and blend in for your life,” he said. “If you’re financially disadvantaged [and] dependent on your parents, you need to start making plans to make yourself financially independent of them so that when they come, all they can do is make noise.”

Tolu, who’s from Nigeria’s Southern region, maintained that he has remained closeted because of well being. “I’m sure I don’t have to worry about getting attacked or beaten or murdered or anything like that,” he said. “But there’s definitely the issue of jeopardising the relationships with my loved ones. I’ve already lost a girlfriend because of my being an atheist, and there’s an uncertainty about how my family and other friends would feel about it. I have revealed my identity to very few people, but they were safe options who agreed to keep my secret or were fellow skeptics themselves.”

“Ultimately, my advice to any young agnostic or atheist out there is to weigh their situation. You know your situation better than anyone else. If you know they won’t be able to take it well or you cannot confidently tell how your loved ones will take your skepticism, it is best to keep it a secret, especially if they have any leverage against you.”

Emotional buoyancy might have to be considered as well. Families could isolate an atheist member or intrude on their privacy. Asked why he hasn’t come out to his family, Funmi*, 20, said his relationship with them would be affected. If he does, his nuclear and extended family would be on his case, calling and trying to talk to him. “At this point, I still need them to exist. I don’t want that kind of invasiveness into my life.”

Igwe deals with his share of familial hostility. “There is tacit hostility towards me and my freethinking disposition,” he said. “Nobody wants to kill me, but they’ll try to suppress any obviously freethinking initiative. But, I am the first son [and] it goes with [a] certain level of power relations, so people just have to deal with me not because they like me or they approve [of atheism].”

When his father, also an atheist, passed away, the family insisted on a Catholic burial. Reluctantly, he complied. Now, he faces the same risk of being buried as a Catholic, but he is determined to prevent that. “I’m making sure nobody insults my memory,” he said.

Grace*, who had been leading his parents’ congregation in prayers since he was seven years old and once expected to become a pastor, lost financial support from his church when they suspected his wavering faith. They offered help—if he returned to Christianity. He refused.

“That sad experience taught me to never reveal what I believe anymore in life,” he said.

The Cost of Atheism

Atheism in Nigeria is costly. Charles, though an evangelical anti-theist, admitted he was lonely offline. He joked that he was still looking for a day he’d see someone thumb through atheist content on their phone inside a public bus. When asked if he’s free to express his atheism the way religious folks do their religious views, his answer was blunt: “No.”

Asked what he would change if he could, Charles expressed a sentiment many others interviewed for this story share: a secular government. “Freedom of religion cannot work without the government being free of religion,” he said. “[You should] practise your religion freely [and] not disturb anybody.”

Igwe envisions atheism as a force for enlightenment. “Theism has occasioned stagnation and darkness in various aspects of life. It has held humanity back, and hampered moral and intellectual progress,” he said. “Atheism needs to morph into a proactive and progressive philosophy, a liberation ideology that frees humans from debilitating dogmas of faiths and the smouldering effect of fanaticism. I hope that atheism becomes a form of emancipation or liberation atheology that enables human flourishing and enlightenment. It is only atheism as an anthem and enabler of liberation that will offset theological deficits and limitations and free humans from the shackles of theism and supernaturalism.”

For Tolu, the dream is simpler: that relationships aren’t destroyed over a lack of belief. “Yes, there is definitely a negative stigma people have concerning atheists in Nigeria,” he said. “It seems a lot less violent in the South than the North but there have been several relationships between people affected simply because a person simply doesn’t believe and I believe. That has to change.”

* Names changed for safety

Edited/Reviewed by: Samuel Banjoko, Awom Kenneth and Uzoma Ihejirika

Illustrated by: Rex Opara

Som Adedayor is Nigerian. His writings have featured or forthcoming in The Republic Journal, Lolwe, adda stories, The Offing and The Lagos Review.