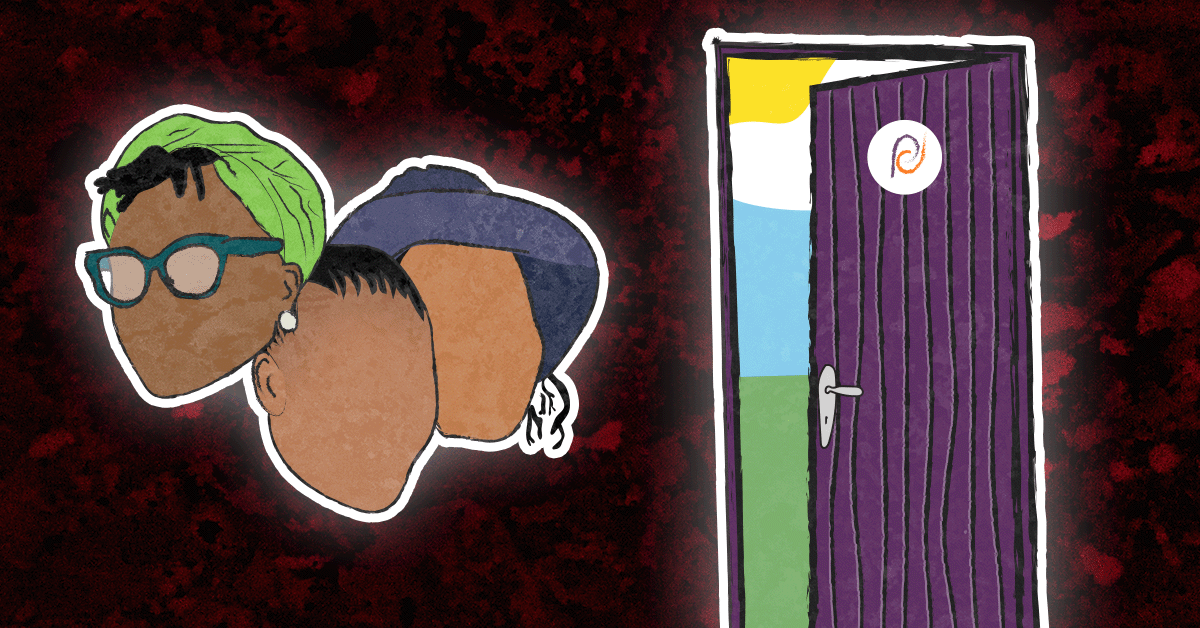

Behind every purple door in this Zimbabwean community, someone is ready to assist women facing abuse

- In Epworth, elderly women trained to be community advocates have painted their doors purple to signal safety during the time of need for abused women.

On a November night in 2023, Mercy Matovera* escaped from the relentless brutality within the walls of her own home. For far too long, she had endured her husband’s frequent fits of rage, with physical blows that came two or three times a week.

But on this fateful night, Matovera reached her breaking point.

The heavy shadows offered her a fleeting sense of safety as she stumbled along the dusty path, her heart racing with adrenaline. Desperate to shield herself and her nine-month-old baby girl strapped to her back, she embarked on a perilous journey in search of sanctuary.

“When I saw the light of a lantern through the window of one of the houses that were close to the pathway, I quickly stopped and walked towards the house,” says Matovera.

She knocked on the door, hoping that she could find shelter, but the house owner refused to open the door to “strangers.” Instead, she urged Matovera to seek help elsewhere, to try another door; maybe she would find someone willing to help a stranger.

Luckily, Matovera found that house. It was a house with a purple door.

“Behind this (purple) door, I found a middle-aged lady who, without any hesitation, asked me to come inside and offered a cup of water to drink,” Matovera recalls. “She told me that her name was Melody Nyakudanga, one of the elderly in the community.”

Nyakudanga (65) is one of the senior citizens in Epworth, a peri-urban community about 17 km from the Harare Central Business District in Zimbabwe.

She gave Matovera something to eat and a place to sleep. “[Nyakudanga] assured me that everything was going to be okay,” says Matovera.

In Zimbabwe, gender-based violence (GBV), which encompasses three main categories—Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), sexual abuse, and child marriage—remains a silent epidemic, particularly affecting married women.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), approximately 1 in 3 women in Zimbabwe aged 15 to 49 have experienced physical violence, while 1 in 4 have faced sexual violence since adolescence.

In November 2023, during the annual 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) revealed that about 18,907 cases of domestic abuse were recorded across the country between January and October, of which 16,444 were reported by women while 2,463 cases were reported by men against women. During the same period, 26 women lost their lives due to GBV.

The statistics indicate that GBV cases in Zimbabwe have been on the rise; 17,244 cases were reported in 2013, and the same period showed a 9.6 per cent rise.

National Police spokesperson, Assistant Commissioner Paul Nyathi urged communities to continue giving credence to the issues of peace and tranquillity in families.

“When couples have challenges, only engagement and discussions can solve the differences, and in those circles that we live, let us help each other and solve matters without any violence,” he tells Minority Africa.

Tragically, violence has resulted in loss of life, with some women resorting to suicide due to lack of support.

Purple Door pioneer Chipo Tsitsi Mlambo of the RhoNaFlo Foundation—a facility-based safe and quality childbirth— believes societal norms play a significant role in perpetuating GBV.

“According to our African belief, girls are raised to believe that they should not question or challenge any form of behaviour of their husbands,” Mlambo says. “They are taught and encouraged to endure pain in silence to protect marital bonds, making it taboo and disrespectful to report abusive partners to the police.”

Rooted in cultural norms and social structures, gender-based violence, especially IPV, is often used by men to maintain control over women within marriages, and usually, survivors bear not only physical scars but also emotional wounds that persist throughout their lives.

In 2022, to break this cycle of silence, Mlambo, working with older women in Epworth who for years have seen and lived with this kind of pain, established the Purple Door Initiative where they would identify strong and warm individuals to provide safe havens to desperate women and girls suffering gender-based abuse.

“For me, Epworth is a community where young girls are getting married at a young age due to poverty,” Mlambo says. “If you ask that young girl today if they can report any form of abuse to the police if need be, they say no, they cannot.”

According to her, the colour, ‘purple,’ signifies a safe space for any woman who needs support in desperate times of abuse.

“Most of them fear the police, maybe due to age. They are kids,” Mlambo states with concern.

“Working with the community, we decided to train community-based advocates to become the first port of call during the time of need of abused women, and we are looking forward to introducing this initiative in other areas across the country,” she adds.

Alous Nyamazana, a director of Fathers Against Abuse, an organisation working to combat abuse by involving fathers and young men, states that gender-based violence issues require collective action and awareness and applauds the pioneers of the Purple Door Initiative.

“It’s time to empower survivors and challenge harmful norms, fostering a safer environment for all,” he says.

Nyakudanga concurs, saying that Epworth has never been a safe place for women.

“As someone who has been living in this community for more than 30 years now, I have seen the worst where women lead a miserable life at the hands of their husbands,” she says. “Most of the women are dependent; they cannot fend for themselves, considering that they get married before they can even finish school.”

Nyakudanga further explains that the situation was so bad that when Mlambo discussed the idea for Purple Door Initiative, “We as the elders of the community agreed and had our doors painted purple, a symbol of a safe space.”

“Now, most people in my area know that behind every purple door, there is someone ready to assist them when facing any form of abuse,” she adds.

According to Mlambo, once victims get to the respite (home with a purple door), they get a place to live for a maximum of seven days, receiving counselling from trained advocates. If necessary, advocates will accompany them to report their cases to the Victim Friendly Units at the police station.

“However, a challenge that we have been facing is when victims are supposed to report the matter to the police and the women hesitate, saying they cannot get their husbands arrested,” Nyakudanga says. “In such a scenario, we would engage both their parents and try to get their issues settled so that they can live with each other in peace.”

Nyakudanga adds that through this approach, many marriages have been saved, and she has witnessed some husbands change their ways.

In Matovera’s case, she is now back with her husband.

“We have been going for counselling sessions at Nyakudanga’s house and I can see the changes in his behaviour,” she says. “[It is] something promising.”

* Names have been changed to protect identities

Edited and Reviewed by: PK Cross, Uzoma Ihejirika, and Caleb Okereke.

Regina Rumbidzai Pasipanodya is an award winning multimedia journalist based in Harare, Zimbabwe. With over five years of experience, she has worked as a freelance reporter, providing media consultancy, and created multimedia content. Regina’s primary focus is on human interest issues, and she is deeply committed to amplifying the voices of the Zimbabwean community, addressing social, economic, political, and environmental concerns. Since 2013, Regina has collaborated with both public and private partners on documentary projects aimed at raising awareness about community issues. Beyond her journalistic pursuits, she enjoys watching documentaries, traveling, indulging in writing and reading novels and magazines. In 2023, Regina received notable recognition: she was honoured as the SOGIE-Northern Region Reporter of the Year (NJAMA) and she secured the 2nd Runner Up position in the Isu Elihle Awards 2023 (Media Matters Africa), an award that celebrates those who give voice to children’s perspectives.