The pressure to conform: How queer Nigerians navigate marriage expectations during the holidays

- Questions and remarks about marriage are uncomfortable for queer Nigerians like me, who already find it difficult to find love and constantly face homophobia.

At twenty-six, my hometown and family gatherings have become places where I have been subjected to gossip and suspected of being a ritualist. A far cry from what it was for me growing up; a place to meet all my extended family members, smile at my grandmother, and see people who are one.

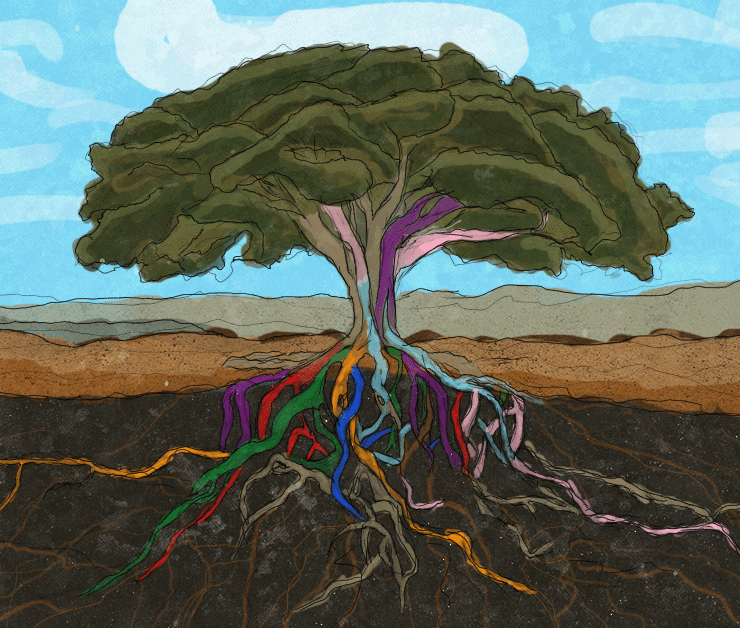

I was born in Lagos, Nigeria, raised by relatives, and attended a missionary secondary school. I have had to battle the internalised homophobia I learnt from religion and school. But growing up loving Igbo traditions and learning that, unlike culture, religion is unchanging, I became more drawn to my culture as I came to accept my sexuality.

But once you reach a certain age in Nigeria, marriage conversations become recurrent. Since I refused to get married, I have had to avoid my relatives and family gatherings, trying to evade conversations around marriage. These conversations start with relatives giving subtle remarks or asking, “what are you still waiting for?”, “Hopefully, you’ll be inviting us for a naming ceremony soon”, or, “I think I have found a perfect girl for you. I know how you like them.”

It’s an experience that Inno, a 28-year-old gay man, aptly captures, “Returning home for Christmas and being at family gatherings was fun when I was much younger. As an adult, however, it became harrowing for me for two reasons. First, the gatherings became more of an avenue for family members to show off. Then talks about marriage started creeping in, like, “When you are ready to marry, make sure to marry from here or there.”

Questions and remarks like these are uncomfortable for queer Nigerians like me, who already find it difficult to find love and constantly face homophobia.

In Igbo culture and across our societies, without marriage, you are nearly nothing and it is quite easy for your opinions to be discounted. When a man gets married, your opinions are respected, and your social class becomes higher because you traditionally have someone you lord over in the home.

For women, marriage is different, “You do get some regard as a woman, which doesn’t last if you don’t ‘provide’ a child six months after the wedding. If you do provide a child, make sure it’s a son. Either way, you remain a second class citizen,” says Wendy, a 27-year-old pansexual woman.

For Wendy, conversations around marriage have existed since she could count her fingers, and they have only gotten brazen as she grew older. “As a teenager, you are warned to move carefully so you do not bring shame to your home and end up unmarried. They start matchmaking you with random boys or men, so you have an assured husband after SS3.”

Despite this, Wendy is an outlier; her parents already know about and accept her sexuality, even though they still blame the devil. But her parents knowing doesn’t make it any easier because marriage is not an affair for just your parents; it’s an affair that concerns your relatives. That means when you are of age, close and even distant family will quip to find out what is delaying you from bringing a man or woman home.

Like every person that travelled to their hometown over the holidays, Wendy travelled too, but she didn’t escape those scary moments and gossip. “I travelled this December, and they pestered me like they usually do over the phone, but I don’t care,” Wendy says.

Questions around marriage are often not well-intentioned. “It’s for their egos, to be honest, that ‘none of our daughters died in their father’s house.’ They don’t care if you live or die. If you die, better do it in a man’s house,” she adds.

Even when these questions are well-intentioned, they alienate LGBTQ+ folks from our relatives. Holidays and family gatherings, which we’ve always seen as places where we come for relief have morphed into a space we shiver at because we are not welcome to be our true selves.

Though I am not yet at the age where it’s persistent, I have developed some sort of fear whenever a family member wants to speak to me. I assume it might be a conversation about my sexuality and other related things.

I know how to shun friends with their questions about romantic relationships, but with family members, I am overwhelmed with trepidation, and it shows in my reactions, raising more questions.

I have developed anxiety concerning straight men gathering and discussing marriage and heterosexual relationships. During my last trip to the South East, I tried ignoring family meetings. I shunned a gathering of my relatives where they discussed societal issues for a long hour. I know long discussions like that come with personal prodding. They might not necessarily ask me about bringing a wife home, but my fear of gatherings like this exists because they are mostly about traditional and conservative family values.

For LGBTQ+ Nigerians, withdrawing from our families is another way our safe spaces are constantly being eroded. In public, the government stifles LGBTQ+ rights, while at home, we are forced to hide and saddled with marriage expectations by our relatives.

Non-governmental organisations like Oasis, run by Matthew Blaise, a queer activist, are one of the few safe spaces where LGBTQ+ folks like myself can gather to smile and make ourselves happy during the holidays, finding love outside our traditional families, away from what we have learned about blood being thicker than water.

Still, conversations around marriage make me wonder if I will ever fit into this culture I have come to cherish. Especially knowing that no matter how good I have been all my life, being a gay man nullifies everything, and I would constantly be faced with questions about marriage.

Edited by Samuel Banjoko, Caleb Okereke, and Uzoma Ihejirika.

Obinna Tony-Francis Ochem is a full-time freelance writer navigating gender, class, sexuality, climate change, and shape-shifting monsters. He is an alumnus of the Lolwe Fiction Workshop facilitated by Zukiswa Wanner and SprinG '20 cohort writing mentorship programme. His works are published on different platforms which can be seen here.

Wow. Very impressive.

It’s always nice buckling up pieces with real-life experiences. This was a brilliant write-up.