Jinja, Uganda (Minority Africa) — Cloud did not know that he was different until the year he turned 11. It was the same year his family moved from the Acholi region in Northern Uganda to Jinja in the East where the Basoga people dominate.

Alongside his 16-year-old brother, he was enrolled in a boarding school where this difference was further exemplified.

“Everyone spoke to each other in a language we didn’t understand, they ate different foods, and most of them even looked different,” Cloud, who is now 26 years old, tells Minority Africa. “Our people are typically tall, lean and dark-skinned. That look is celebrated and looked for in models now but back then it really wasn’t.”

By “our people,” he is referring to the Lango, Acholi and Japadhola tribes from Northern Uganda who have historically been marginalized.

The recent history of Northern Uganda is highly marred by the conflict between the Ugandan government and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), which raged on for two decades up until 2006. It left about 1.8 million people displaced.

This conflict exacerbated poverty and had long-lasting effects on different areas of life such as education, infrastructure, people’s assets, and wellbeing – leaving the region with some of the worst development indicators in the world.

Primary school attendance declined by approximately 20% between 2013 and 2018, and only 5% of those that were displaced by the war went on to complete their secondary education. There are also more disturbing trends of human trafficking– including a case of 35 girls who were found in Kenya and returned after being trafficked from the Karamoja region in North-East Uganda in August 2021.

A report by ODI stated that: ‘Northern Ugandans continue to live with a sense of loss, injustice, neglect and a widespread sentiment that post-conflict life has not lived up to its promise.’ Because of social factors and sentiments like these, many families like Cloud’s moved to different parts of the country to seek a more stable life.

“Just my name was a big giveaway that I wasn’t from the same place,” said Cloud, who at the time went by his birth name, which he inherited from his father. As a young boy, he found it hard to take pride in a name that his peers teased him about, and wished that he could change that aspect and many others about himself.

Emmanuel Weere, a 36-year-old social researcher and development worker from Uganda explains that tribalism is a long-standing issue in Uganda, dating back to the days of colonialism.

“The way that the British divided the country and assigned power has a lot to do with how things are now and perceptions people hold until today. Whereas power was previously assigned based on war and natural wealth, it was now centralized and re-distributed by the British,” Weere explains.

“Once Kampala became the capital city, those in close proximity received better education, took administrative jobs and made more money, which then translated into a sense of superiority amongst those from that area,” he says. “The north being one of the farthest regions from the city, coupled with the civil war, caused it to be perceived as a low-status area. This inequality carried on long after Independence, and is fueled by stories that hold sentiments of prejudice.”

“Some of the discrimination was subtle and some of it wasn’t,” Cloud recalls about his experience. “It was hard to find a friend group to sit and eat meals with as they usually talked in a different language. The teachers would sometimes say things like ‘That’s why your people are stupid’ right in front of the whole class.”

“Dating was impossible, as no girl wanted to be seen with someone that was considered low class,” he adds. “The first few months were a miserable time, and I often questioned why our parents had brought us here.”

With no clear friend group to pass the time with, Cloud spent his weekends in the common area watching the shared TV with a few other students. Most of the girls wanted to watch soap operas while the boys preferred football. To reach a compromise, they usually ended up watching music videos. That was how the world of dance was introduced to Cloud. He watched hours of pop, hip-hop and rap music videos on MTV and TRACE channels.

“At that time Chris Brown and Usher were the hot artists, and those guys could dance,” he says. He also noticed that the girls liked the dancing stars. “Whenever they’d come on the screen, you’d see the girls get excited and the boys look on with a sense of admiration. There was power in that, and I thought maybe if I could learn a few moves then that could become something really interesting about myself.”

Cloud started practicing behind the dormitories or in empty classrooms at night, replicating what he saw on the screen. His debut performance was at a school dance, which is commonly known in Uganda as Kadanke and is set up similar to a club setting.

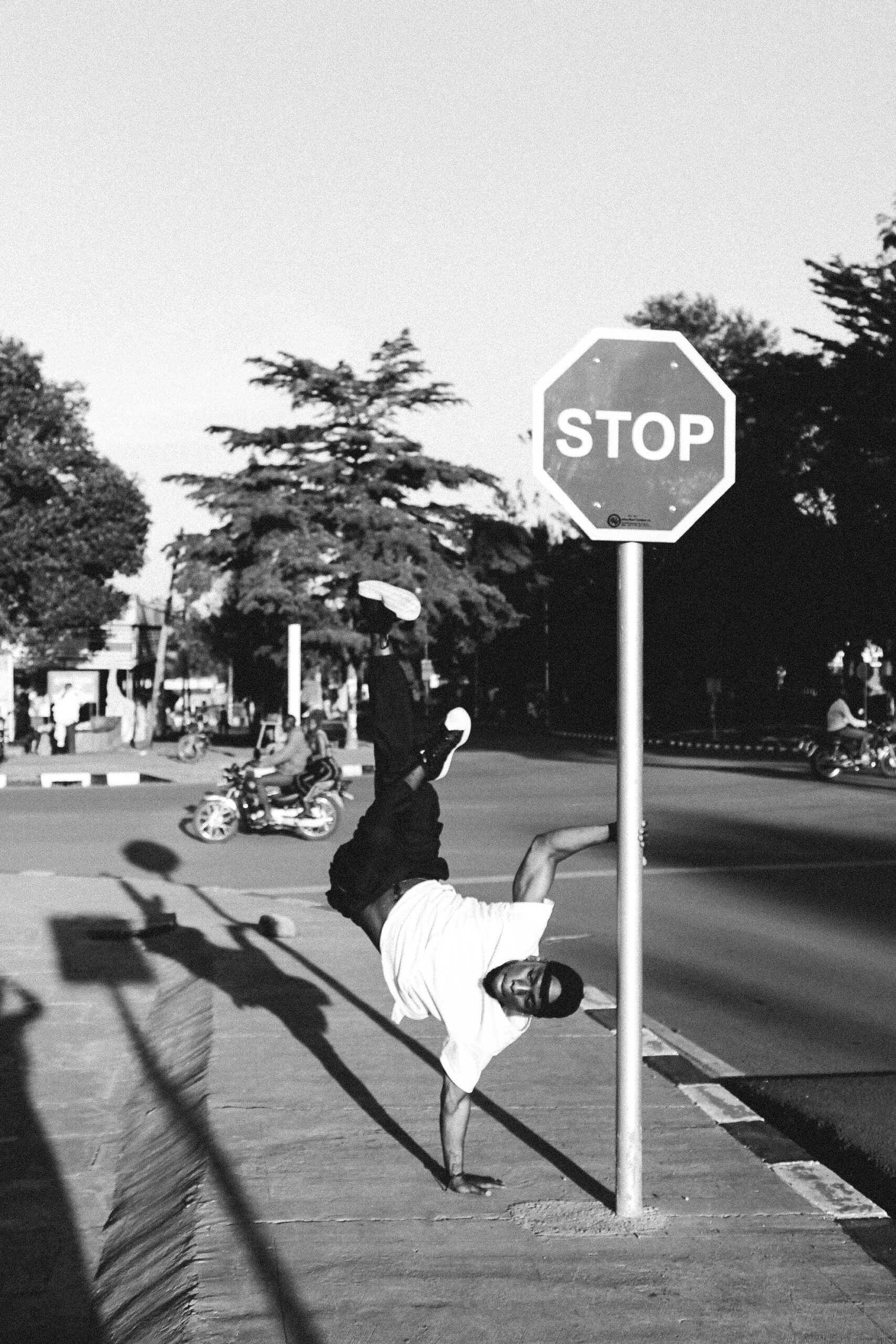

“We used to have Kadanke sessions about once a month, and there everyone was free to dance as they pleased and bring out their best moves,” Cloud says. “The best dancer would usually become surrounded by people, cheering them on and copying their moves. I was so surprised when this started happening to me, and it made me feel so proud and popular. I remember one of my friends commenting on my legwork, `It’s like you have no feet man, you move like a cloud’.”

And that reference birthed his new identity, Cloud. He continued attending every Kadanke session and then started performing at assemblies and eventually at inter-school events and talent shows.

“Getting to perform in front of another school was truly a ticket to fame in high school,” he says. “Once people started knowing me as a dancer, it was like all the negative associations that came with my tribe were forgotten. I even got a girlfriend, and for my 15-year-old self, that was making it.”

After high school, Cloud took a few years off schooling to pursue a career in dance and save up money before he enrolled in university. During that time, he joined a dance crew called Street Dance Force and they would practice and perform together, while incorporating different art forms such as rap and DJing in their work.

Through Street Dance Force, he met his friend, Ram MC, and together they founded Talanta Youth Movement, which uses hip-hop as a tool for positive social change. They train young men in Jinja in hip-hop, dance, rap, and graffiti, giving them a creative outlet, a safe space and a chance to perform.

“We wanted the next generation of kids in Jinja to be good people and good dancers,” Cloud says. “We targeted children for whom this would be an unlikely outcome; those living in the ghetto, those who didn’t have an education, and of course people that felt out of place like me. I knew how much dance had helped me in my own life and believed it could do the same for these young boys. As men I feel it is easier to get lost in our heads and succumb to bad deeds when we feel discriminated against, and this is what I’m hoping to avoid.”

Eventually, Cloud had to pause his work with the organization to pursue his degree in social work at Kyambogo University in Kampala. He recently graduated and hopes to use this access and qualification to be able to reach even more youth, and spread the gospel of breakdance for positivity, fitness, acceptance and social change.

“As people move more freely around the country, and schools are populated with students from different tribes, we [should] think of ourselves as just Ugandans, as opposed to different tribes,” Weere says as regards the way forward. “Ideally, we should be able to break free of all forms of sectarianism, and just acknowledge that we are all human. First and foremost.”

While the region of Northern Uganda continues to heal from the wounds of war, Ugandans continue to contend with its effects on both the people and perceptions of that area.

“People are taught to reject difference, instead of being curious or accepting of it,” Cloud says. “People from Northern Uganda still face negative stereotypes; I guess everyone does. I think that showing people who you really are can change their mind, and we can also do it through art and dance and stories.”

He adds, “These days, I happily introduce myself with both names, and I wish for everyone the pleasure to do so.”

Edited by Mamaponya Motsai, Caleb Okereke, and Uzoma Ihejirika.

Aida Namukose is a 2022 Minority Africa Fellow. Aida is a 22 year old photographer, videographer and all round creative from Jinja, Uganda. Her specialty is portraits, and she loves meeting new people and capturing their essence with her lens. She hopes to capture and write about stigmatized communities in Uganda, contributing to making a more accepting society as a whole. In her free time she enjoys swimming in the river, learning about spirituality and eating groundnut sauce.